Father’s reflection in marble

After an eight-year hiatus, Asif Rustamov made his return with his second full-length film, “Cold as Marble.” Much like his previous movie, “Down the River,” the central theme revolves around the intricate dynamics of a father-son relationship and the profound traumas that can emerge from such complex bonds. Setting the tone with a blend of jazz melodies and poignant groans, the film unveils a mesmerizing tableau, drawing viewers into the captivating world of the fictional character Agha Bayramov. “Cold as Marble” immediately grabs attention with its scintillating erotic undertones, weaving a psychosexual atmosphere that becomes the hallmark of the entire cinematic journey.

The film ingeniously weaves its narrative threads within the corridors of a museum, a place steeped in the memory of the enigmatic oil magnate and philanthropist, Agha Bayramov. It’s within this hallowed museum that our protagonists come to life – Natavan Abbasli, portraying a young woman who works diligently amidst the artifacts, and Elshan Asgarov, playing the role of a son entangled in the allure of a married woman. Displaying a bold departure from conventional storytelling norms, the director fearlessly exhibits his audacity, hinting at a cascade of innovative concepts that promise to unravel as the plot unfolds. The unorthodox introduction and narrative structure stand as a testament to the director’s willingness to explore uncharted territories and present audiences with a fresh and daring cinematic experience.

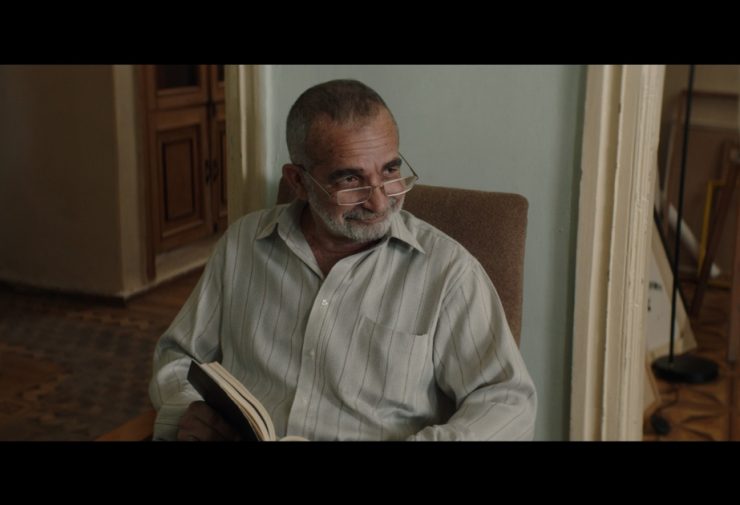

The return of Father (Gurban Ismayilov) disrupts the rhythm of daily life, casting a shadow over the familiar routines that had settled in his absence due to a past crime. Adjusted to the stringent laws of prison existence, Father initiates a suffocating influence over his son, permeating every aspect of his behavior with demeaning remarks and asserting dominance by amplifying his physical and emotional prowess. Each of Father’s calculated actions exudes a manipulative air, while the intricate layers of his persona form a cornerstone for unforeseen twists and turns throughout the film.

The director masterfully maintains focus on this triangular dynamic, woven tightly between the father, son, and estranged girl, propelling the narrative’s dramatic momentum to its culmination. Naturally, there is also a mother figure, wearied by the haunting remnants of the past, whose presence underscores the poignant backdrop against which the tale unfurls.

The son, a struggling artist, finds himself trapped in the clutches of his own limitations, lacking both influential connections and the flair for acting that could propel his career. His authentic self, while true to his artistic vision, becomes a stumbling block. This reality becomes painfully evident as exhibitions remain elusive, his artistic creations linger in obscurity, and he reluctantly turns to painting tombstone portraits for meager earnings. The film provides a glimpse into the Azerbaijani art scene during the protagonist’s introduction, allowing us to envision the prevailing artistic landscape. However, this exploration remains fleeting and episodic, merely brushing the surface without delving into a comprehensive depiction. The son’s artistic setbacks, his struggle to bring his canvases to life, and his inability to achieve recognition all remain confined to a personal sphere, serving as a catalyst that intensifies his fraught relationship with his father.

The absence of his mother casts a looming shadow over his artistic expression and life at large, representing a pivotal trauma. So profound is a wound that he avoids setting foot in his parents’ bedroom.

The individual engrossed with this enigmatic chamber, delving into its concealed intricacies and even feel suspicious is in fact a young woman

She insists on confronting the trauma because she is sick of the son’s complex. Upon stepping into the room, an expectation is set to trace the footprints of the past, yet the narrative veers away from this anticipated trajectory. Although the film seemingly promises to delve into the depths of the Girl’s character, potentially even casting her in the mold of a conventional “Femme Fatale,” it only scratches the surface of this transformation. Consequently, the portrayal remains largely superficial. As a result, the ambivalence shrouding the girl’s aspirations and yearnings, coupled with the underlying motives driving her actions, detrimentally impacts the film’s overall dramatic framework.

The convergence of these three characters and the intricate relationship triangle they form serve as catalysts for the son’s escalating obsession, jealousy, and anxiety. These emotions intricately shape his behavior. During these moments, the director deftly weaves a Hitchcockian atmosphere of suspense, propelling the film’s dynamics to new heights. The introduction of the Father into the equation, his intervention with the desired woman, further amplifies the intensity of the love narrative, an achievement that becomes a cinematic language in its own right. While the metamorphosis of characters, the evolution into distinct personas, predominantly centers around the Father and the Son, the world of the Girl remains relatively unchanged. Father’s distinct black attire is conspicuous right from the outset, but it undergoes a transformation as he assumes the role of a Mullah, transitioning to a pristine white outfit. This deliberate change in clothing reflects not only his evolving professions but also serves as a visual representation of his manipulative nature and the seamless shifts between various characters he embodies. The unresolved conflict between the Father and the Son remains devoid of catharsis. The Son lacks the requisite strength for a confrontation, and Father adeptly exploits this vulnerability to his advantage. They encounter each other along a railway line in just one scene, both under the influence of alcohol. Through a medium-close-up shot, the viewer is presented with the juxtaposed images of the father and son, separated by the railway bars. This visual element of bars becomes a poignant symbol, representing the insurmountable obstacle that stands between them.

The father and son characters loom large at the heart of the narrative, often overshadowing the role of the young woman, whose presence seems to serve more episodic purposes. The girl appears almost devoid of personal agency, merely conforming to the role assigned to her. Consequently, the film misses an opportunity to introduce fresh perspectives or innovative ideas concerning women. Despite initially hinting at exploring psychosexual undertones and delving into an increasingly obsessive theme, the narrative fails to fully embrace these aspects. Instead, what unfolds is a predominant spotlight on the conflicts between the father and son, sidelining the potential depth of the father-son-girl -mother quartet. This approach perpetuates a largely male-centric viewpoint, unintentionally marginalizing the narratives of the female characters. The result is a narrative that inadvertently or knowingly sidelines women’s stories, with the male characters taking center stage.

As the film reaches its conclusion, it adopts a critical stance towards the events that transpire, yet it notably assigns a significant portion of blame to the female characters. This narrative choice gives rise to yet another problematic instance within Azerbaijani cinema, one that appears reluctant to transcend the confines of a male-dominated perspective. In this portrayal, women are unfairly burdened as the prime culprits, perpetuating a notion that conveniently allows men to shift accountability for their actions onto women. This approach and viewpoint stand in stark misalignment with the ethos, ideologies, and contemporary sentiments of our era. While such a portrayal might have been understandable within the context of the 1960s, it now falls out of step with the inclusive and progressive ideals that define modern times.

The actors’ connection with their respective characters in the film feels innate, allowing them to seamlessly convey the personas they’ve crafted to the audience. Elshan Asgarov’s remarkable transformation from a bohemian, creative individual to a more traditional archetype, along with Natavan Abbasli’s captivating gestures and facial expressions that cast a spell on men with a magnetic allure, contribute significantly to the story’s resonance.

The true triumph of the film lies in Gurban Ismayilov’s portrayal of two contrasting personalities – akin to night and day. He adeptly embodies a remorseless sadist, unflinchingly capable of the most heinous deeds, while also embodying a meek penitent who seek refuge in God. With each step he takes, Ismayilov showcases mastery, effortlessly oscillating between ruthlessness and compassion. His rendition of the manipulative father is executed with such precision that it emerges as one of the finest performances of our independency cinema years Every scene graced by Gurban Ismayilov’s presence is electrified by his dynamism and vitality, captivating the screen and holding the viewer’s unwavering attention.

The film’s cinematographers, Oktay Namazov and Adil Abbasov, skillfully navigate between the roles of observer and active participant through their camera work. This dynamic approach effectively captures the stress and tension coursing through the characters’ experiences. By maintaining proximity to the characters, the camera draws viewers into the narrative, transforming them into engaged participants of the process. The camera serves as a seamless conduit for conveying the story’s essence, its fluid movement enhancing the storytelling experience. This success owes much to the adept editing of Rza Askerov, who masterfully orchestrates the rhythm of the film. The seamless transitions between scenes, devoid of any unnecessary delays, further contribute to the film’s overall cohesiveness.

In wrapping up, “Cold as Marble” boldly kicks off with audacious moves but struggles to sustain its initial freshness and atmosphere throughout its duration. The primary culprit behind this lies in the film’s inability to find a fitting resolution for its thematic elements, opting instead for a solution rooted in archaic perspectives. This departure from the director’s previous work is palpable, as Asif Rustamov showcases an improved synergy with his actors, resulting in performances that elevate the film significantly. At the end of the film, the audience is left with indelible images – a father’s visage as cold as marble, a son consumed by the icy chill of this very countenance, and guilty women.

Haji Safarov