Where are you rushing off to? The public eye is upon

Once Upon a Time “In this Southern city”

In March of this year, Azerbaijani literature and art, particularly in the realm of film, bid farewell to one of its most prominent figures, Rustam Ibragimbekov, who passed away at the age of 83. On this day, our world of literature, cinema, and theater warmly embraced his rich creative legacy.

A fresh, independent phase of creativity unfolds after an artist’s passing. While alive, creativity isn’t entirely unshackled. The artist’s personality keeps a watchful eye, safeguarding against criticism and striving to stay at the forefront of attention. There’s a perpetual dissatisfaction with their own work, a constant inner dialogue: “I should have depicted that scene differently, condensed that episode, delved deeper into that character, and brought the reader closer.” Consequently, they continually attempt to write in a new manner, to craft novel effects, and to astonish their audience even more. They write, break apart, and rewrite. Let’s concur that, when the author is alive, their “self,” their personality, takes precedence over their creative endeavor.

The second, more extensive, and truly independent phase of creativity begins when it becomes “ownerless.” It’s a time to appreciate the work for what it is, detached from the identity of the author. For a great writer to truly shine, they must find an equally great reader, one who can meet them on their level. This connection doesn’t happen overnight, an hour, a day, a year, two years, or even five years. Sometimes, it can take even longer. Only when a great reader emerges can we genuinely speak of the greatness of the work. This reader-analyst, who delves deep and uncovers the hidden themes, worldviews, and concealed purposes within the artwork, has the power to resurrect the departed author, much like Sheikh Nasrullah’s (by Jalil Mammadguluzadeh “ The dead” ) legendary tales.

However, for those of us who are contemporaries of Ibragimbekov, there’s no need to wait for a great reader to offer new interpretations and discoveries. Today, we can readily embrace works like “9th Mountainous Street,” “Park,” “Like a Lion,” “Investigation,” and Rustam’s creative oeuvre as a whole.

Each of Ibragimbekov’s works, whether in the form of plays or films, has provoked a spectrum of opinions. This stems from the fact that he delved into a world rife with contradictions, openly addressing one aspect while not concealing the existence of another. He was an author known for his controversial and multifaceted storytelling.

While he began his writing career in the sixties, I would place him more in the category of the 70s generation rather than the 60s. The 60s carried a greater sense of melancholy; their hopes and belief in a new era had already faded. Particularly after the Soviet tanks rolled into Prague, Czechoslovakia, in 1968, it became evident that the prospect of moderation had vanished. The status quo remained unchanged. The aspirations of those years went unfulfilled, and the days of living with hope had already passed, though many were yet to realize it.

The day passed. In the very phrase “The day passed”, which happens to be the title of one of his films, we gain insight into the language and perspective of the sixties. However, Rustam Ibragimbekov sought his adventures in the seventies, eighties, nineties, and beyond, and life generously supplied him with an abundance of material. Life, in fact, always provides us with material; the trick lies in recognizing it. There’s much to observe, but you must have the foresight to anticipate events. In essence, one needed to be both a custodian and a seer. There’s no other way to craft fiction. If you truly live, you live within this world, and in this world, you won’t be lacking for material to fuel your writing.

Just imagine a young man working for a magazine or newspaper, in search of a gripping story, who invites two young female journalist colleagues to his apartment with a balcony overlooking the street. He gestures toward the street and, in the words of the characters, points out the neighborhood, saying that today… they will take lives right there. Just imagine their state of mind- Let me emphasize, you must picture this: it’s 1969, the war is over, it’s a Soviet city in times of peace, slogans like “we vote for peace” adorn every corner, and the mantra “my militia protects me” reigns supreme. Yet, this young journalist boldly informs his colleagues of a surreal historical spectacle about to unfold in their neighborhood—a gladiator battle, where one individual will come to take another’s life. He’s not exaggerating. And true to his words, the macabre and fantastical event unfolds, marking the commencement of a film characterized by its harsh realism.

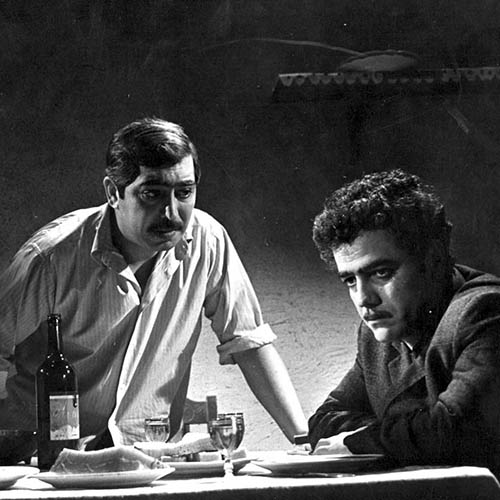

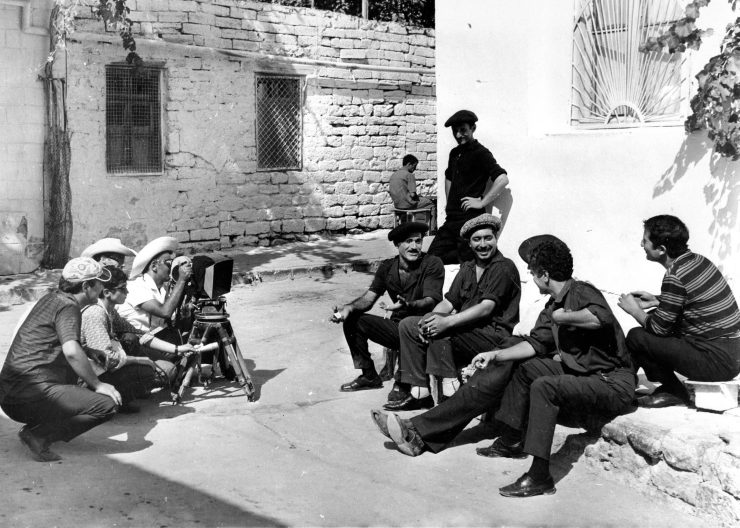

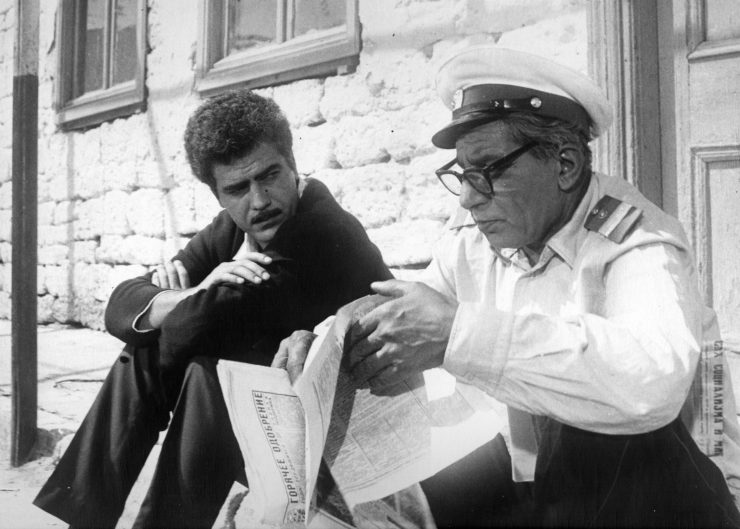

In 1969, with Rustam Ibragimbekov’s script and under the direction of Eldar Guliev, the film “In This Southern City” unquestionably stands as a masterpiece of Azerbaijani cinema. However, even more than half a century later, discussions about this film still stir controversy. Should we indeed approach the events unfolding in this criminalized neighborhood from a moral standpoint? Does the author err in this regard? The crux of the matter is that the depicted events could have been presented within the realm of criminal drama or even through a satirical lens, reminiscent of the style of Mirza Alakbar Sabir.

In the sepulcher’s shadowed realm, I find no fear to tame,

Where Muslim hearts beat strong and free, I quiver in their name.

Within your thoughts, a mystic sea, I sense a potent flame,

In that deep, enigmatic gaze, I shudder at the game.

The people Sabir mentioned foam at the mouth, but fundamentally, his work embodies satire. It delves into the disparity between the satirical character’s intentions and their true inner self. In essence, it portrays how an individual who seeks to intimidate others through force may, when confronted with a superior force, react with fear and even become a laughter stock.

However, “In This Southern City” diverges significantly from the realm of satire. At first glance, the neighborhood often labeled as criminalized is depicted as a microcosm of the world itself, presenting a unique perspective.

At the time “In This Southern City” came to life, Gabriel García Márquez had yet to craft his concise masterpiece, “Chronicle of a Death Foretold”. Within those pages, inhabitants of a settlement guide our heroes toward a murder, while they become mere onlookers. In truth, it unveils a mythological template ingrained in the human spirit. A larger nation invades a smaller one, prompting the larger countries to stand as spectators from afar. They should offer their commentary, denounce, chastise, impose fines, penalties, sanctions, extend compassion, and lend support to the beleaguered. It’s this very script that shapes the tragic play of war.

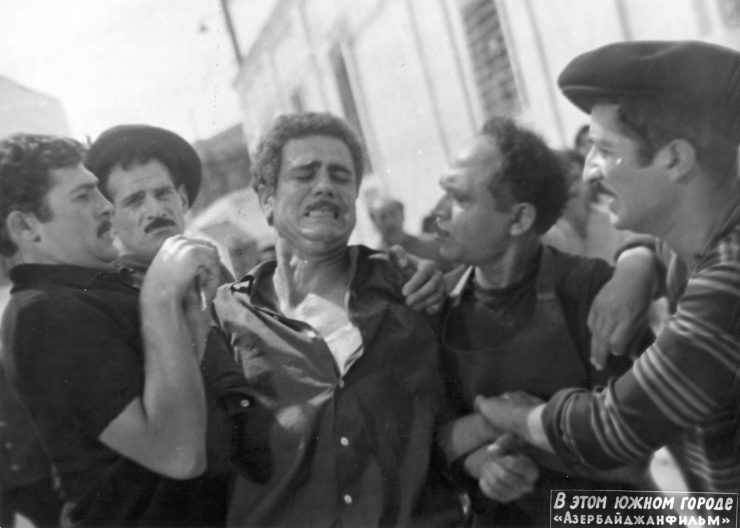

In our movie, the residents of the neighborhood are well aware of the unwritten code that dictates that a newly released individual from prison must exact revenge upon a man working at the beer shop in the neighborhood. This man had led the former prisoner’s wife astray. Failure to follow through with this act means exile from the community. As we mentioned, the neighborhood is a microcosm of the world; there’s no escaping from world. Hence, when Agabala, freshly released from prison, approached the shopkeeper who was attempting to evade him, he uttered these words: “Where are you rushing off to? The public eye is upon us.” Whether we like it or not, we’re bound to enact this performance for them, with me in the role of the executioner and you in the role of the victim. It might sting a bit, but that’s how the script is written. I must commit this act and return to prison, while you must meet your end and journey to the other realm.

May God spare us from ever being a participant in such macabre dramas.

This scene serves as the film’s opening, setting the stage for the overarching theme. The movie, however, delves into entirely different characters: relatively young individuals who have lost their fathers in the war. Rena, one of the journalist girls who was deeply affected by the murder spectacle, begins to document the incident. However, her boss informs her in advance that the article won’t see the light of day in their editorial office. According to him, such an event simply cannot occur in a Soviet nation. From a historical perspective, we must acknowledge the editor’s viewpoint, even though he remains off-screen in the film. The Soviet Union had defined borders, and even within these borders, the reach of the Soviet government wasn’t universal. For instance, the neighborhood depicted in this film lies at the upper reaches of the city, just five hundred meters from the government’s center. In this neighborhood, there was only a single government representative present. Following any incident that ran contrary to party decisions and regulations—please note, only after it had already occurred—the local representative or field militia would report to the higher-ranking authority, who would then arrive to resolve the situation. Beyond these interventions, the government had no other role in the neighborhood’s day-to-day life.

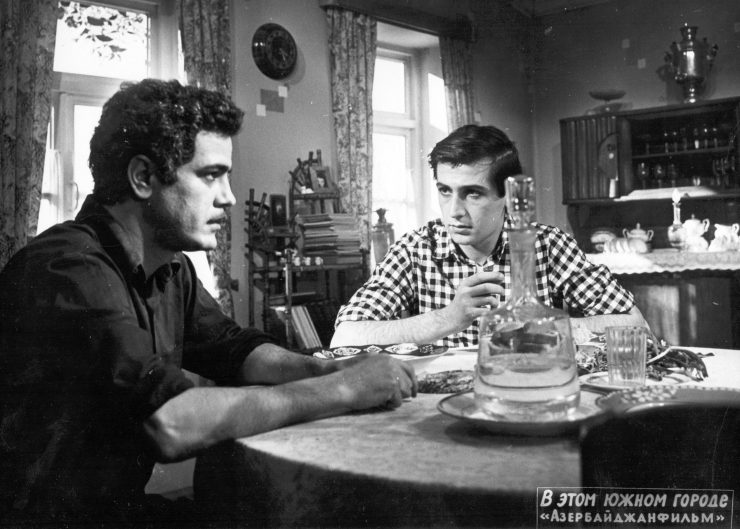

When the topic was banned, Rena dodged in it and decided to write an article about Murad, a young resident of the neighborhood who works at Oil Rocks and is widely regarded as a master in his field. Rena made her way to Oil Rocks to get firsthand information about Murad’s work. During her visit, she conducted interviews with Murad, delving into various aspects of offshore oil extraction. Amidst these discussions, seemingly prompted by her curiosity, she also inquired about an incident that had occurred in the neighborhood that very day.

“Do you think Agabala acted correctly?” Murad, a compassionate and prematurely aged young man due to his responsibilities, had taken on the role of the elder brother at home after his father’s death during the war. Despite his young age, he worked tirelessly at the mill, earning a living, raising children, and ensuring they received an education. Now, alongside his sister, he was busily preparing for Tofig’s wedding, his neighbor whom he had always looked after as a big brother would. Murad, with his profound understanding of life’s hardships and his strong work ethic, couldn’t fathom being associated with any form of wrongdoing, let alone murder. So, when Rena posed the question about Aghabala’s actions, his response was resolute: “No, he didn’t do the right thing.” However, Murad also recognized that the victim bore some responsibility, perverted the woman having taken advantage of her husband’s imprisonment and her brother Babash’s mental illness.

In essence, this murder had its own complex history. Still, Rena persisted with a question that seemed unrelated to Murad’s life, as if for the sake of asking it:

“Would you do such a thing yourself?” Murad was momentarily taken aback by this question, but he swiftly regained his composure and replied once more, firmly asserting, “No. These are remnants of the past.”

The entire drama of the film revolves around the answer to this question: How true and sincere was Murad in his response? It’s a fact that these customs are relics of the past, archaic expressions of a traditional worldview. The dawn of a new era calls for entirely different responses from people. But can Murad truly break away from tradition? There’s something, whether we like it or not, whether we acknowledge its truth or not, that compels us to follow these customs. It’s a matter of honor if we do, and shame if we don’t. One day, each of us will find ourselves in such a situation, an unwelcome day of reckoning. But these “one days” don’t occur just once in a lifetime; they can frequently punctuate our lives. Murad, fully aware of this reality but unwilling to accept it, suddenly undergoes an internal revolution, a transformation known as metanoia in psychology. He’s shaken, filled with regret, and becomes willing to depart from tradition, to repent, and to face the challenges of this new life. He takes his first step along this path. Rena, the interviewer, unwittingly becomes a catalyst for this transformation. Murad decides to take her seriously, despite her being a complete outsider to traditional beliefs, and intends to marry her according to their customs. But does this new life accept Murad with all its challenges?

Rena, residing on the higher rungs of society, naturally regards him from above. Murad’s social standing doesn’t afford him the privilege to ascend, knock on the girl’s door, and pour out his heart. He comprehends that this role is beyond his reach, so he aimlessly roams the city for a while. From the window of her modern city-center residence on the upper floor, the girl casts a sardonic smile at him. “You can only exist as an object of a journalist and writer to me; you’re not something more,” she remarks.

The pivotal moment in this film unfolds when Murad sends Tofig to a provincial town in Russia. Tofiq’s father had tragically lost his life in a battle against the German fascists in a distant Russian city, and he was posthumously honored with the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Now, a statue is being erected to commemorate the hero who liberated this unknown city from fascist occupation, and the hero’s son, residing in a distant southern city, receives an invitation to participate in the statue’s unveiling ceremony. This invitation is fitting because Tofig, as the son of a Soviet Hero, had been imprisoned for refusing to disclose the identity of his neighbor, who made a mess of in the center of a fictional district called Laurent.

Upon receiving the invitation letter from Russia, he is released from the custody of the southern city’s militia department. However, Tofig initially has no plans to journey to the Russian city, primarily due to his lack of funds for the trip. Murad steps in to provide him with the necessary financial support and sends him on his way. While Tofig is engaged to Murad’s sister, he embarks on this journey, not only attending the ceremony in Russia but also deciding to marry a woman there and eventually bringing her back with him to their southern city.

Following this incident, the neighborhood residents, effectively the audience in this unfolding drama, assign roles in the new and tense spectacle – Murad and Tofig. Murad is expected to exact revenge on Tofig for the perceived insult to his family. However, Murad’s sister finds solace in her newfound freedom from Tofig. Yet, this is beside the point; the gruesome show must go on, the audience awaits, the declaration has been made, but the timing remains uncertain, and the moment is anticipated.

In reality, it’s not solely about the neighborhood residents but also about the prevailing traditional mindset. Such grim spectacles typically unfold within the realm of traditional thinking. Nevertheless, Murad upholds his commitment. He participates in the performance but refrains from harming Tofig. The outcome for him remains unknown, but on the rainy day following the play, he ventures alone to the militia department.

This final scene was changed and an essential detail appeared. As far as I know, Rustam Ibragimbekov penned the story “9th Mountain District” after the script of this film. To truly grasp the film’s essence, one must delve into this narrative. It becomes apparent that the events presented in the film are not the result of journalistic investigation conducted by Rana, but rather, they are conveyed through the ramblings of the eccentric Babash, a resident of the neighborhood. In the story, his name is listed as Mishoppa. In reality, there was a man named Mashadi Baba in the mountainous neighborhood—I was fortunate to have seen him in my youth—and people would affectionately refer to him as Mishoppa. He would mimic the sound of a car horn running across, as if he were driving a vehicle. Granted, his repertoire extended beyond just imitating car noises, but the author of “The 9th Mountain District” found this particular detail to be significant. In the narrative, the author follows events along Mishoppa’s route, providing us with a unique perspective based on his outlook and daily routine.

In 1969, William Faulkner’s “The Sound and the Fury” had not yet been translated into Russian, and Soviet citizens, including the scriptwriter, were unaware of this monumental literary work from the 20th century. It’s worth noting that in Faulkner’s novel “The Sound and the Fury,” the saga of a grand lineage is narrated through the perspective of a deranged individual. Similarly, in this narrative, the all-seeing and all-knowing madman, Babash, imagines himself driving a car and beckons Murad and the police officer Mustafa to join him in this imaginary vehicle. In essence, Babash shows them a way out of their predicament. They hop into this “car” and follow the madman, honking along. As mentioned earlier, this ending was altered due to censorship demands. Undoubtedly, this change affected the film’s loss of meaning. Nevertheless, the film’s artistic prowess and symbolism continue to captivate us even today, perhaps even more so than in the past. With each viewing, it unveils fresh themes and deeper meanings.

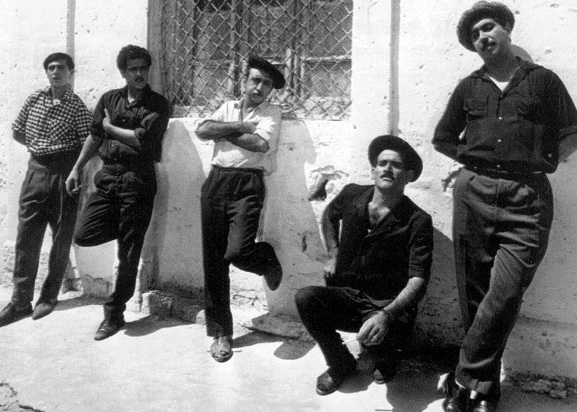

It’s crucial to recognize that this film extends beyond the superficial perception of being just a portrayal of Baku “gadashs”-guys, as some might simplistically view it. Instead, this film serves as the narrative of a southern city that played a pivotal role in shaping the history of the entire nation.

On March 30, 1918, just one day before the tragic events of March 31, (Day of Genocide of Azerbaijanis) Alimardan Bey Topchubashov addressed a gathering at the Committee of Muslim Public Organizations in the Ismailiyya building. He remarked, “Take a look at these fortress walls. The Muslim community that has resided in this city for generations and generations serves as undeniable evidence that Baku is indeed a Muslim city.”

Alimardan Bey Topchubashov’s words were not uttered by mere chance. During that time, Baku was not regarded as either a Muslim or Azerbaijani city. Russian officers had initiated construction projects in the heart of the city, including the construction of a massive church. Crafty Armenians also participated in these building endeavors. Baku saw the establishment of an opera house and performance halls, where renowned artists such as Chaliapin and Komisarjevsky toured. However, these developments held little relevance for us, aside from a handful of Azerbaijani millionaires. However, the construction of a mosque in the city center was strictly prohibited. The Tazāpir mosque could only be erected in the mountainous Muslim districts. The crux of the matter is that, even during the Soviet era, those who prevented Baku from being completely estranged and, as Topchubashov stated, maintained its status as an Azerbaijani city were the inhabitants of the neighborhoods we now colloquially refer to as “Sovetsky.” It’s worth noting that Sovetsky was the name of just one street there, but in reality, these areas had been known as mountainous neighborhoods since ancient times.

The movie “In This Southern City” tells the tale of Baku. Right from the opening shots of the film, even in the credits, you can discern the stark contrast between innovation and traditional values. Let’s focus on the initial sentence from Ibragimbekov’s narration: “The southern city descended gracefully toward the sea, resembling a circular amphitheater. If the seaside boulevard were the front row of this amphitheater, then the 9th mountainous neighborhood where Mishoppa resided had to be sought out somewhere in the distant rear.”

Following the establishment of the council government, just a street was named Sovetsky and it still lingers in memory. However, it’s crucial to note that this place bore no connection to either the Soviet Union or Tsarist Russia. The analogy we can draw here is that ancient Greek tragedy doesn’t unfold upon the stage in front of the amphitheater but rather in the overlooked rows above. Let’s not shy away from this description; the film’s substance and its hidden facets provide us with ample justification for using this term. Within its narrative lies war, heroism, homecoming, the betrayal of Penelope, the vengeful wrath of Odysseus, and even murder…Here, we encounter the chorus, the quintessential element and prerequisite of any tragedy – the inhabitants of the neighborhood. Furthermore, madness finds its place in this narrative. We can’t find such a convergence of these motifs in one instance, not just within Azerbaijani cinema but not even within the broader scope of Soviet cinema as a whole.

The most important thing is that in this film traditional consciousness collides with innovative tendencies. Aren’t tragedies, wars, revolutions, Arab springs, and other events happening in the world today (let’s not enumerate them) born from this contrast? So, it is possible to read the history from the cinema.

“In This Southern City” is a historical film.

Nadir Badalov