Time frozen between two loves

Certain parallels are present between Strange time, co-written by Huseyn Mehdiyev and Ramiz Rovshan, and Michael Haneke’s Amour. In both films, one of the protagonists falls into a grave condition and becomes increasingly disconnected from life, while the characters around them remain uncertain about how to respond to the situation.

In Strange time, the father falls from the roof, and from that day onward his daughter withdraws from the outside world, devoting herself entirely to his care. Amour, on the other hand, centers on an elderly married couple. The wife becomes severely ill and loses her ability to walk. The husband refuses to send her to a hospital, choosing instead to care her at home.

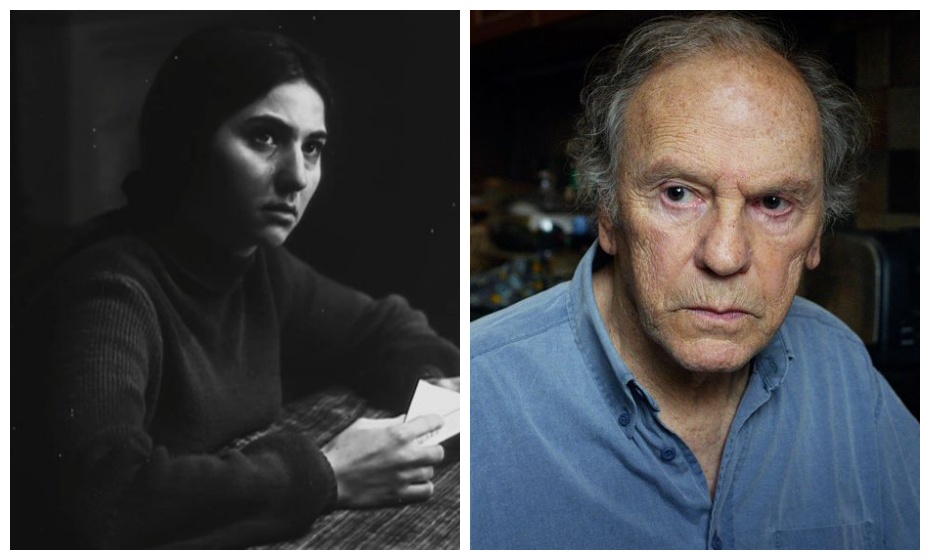

In the opening scene of “Strange time,” we see an elderly man seated in a wheelchair. At first glance, we assume he is dead. Yet as the camera moves closer, we notice that a vein on his neck is still pulsing. This is the director’s subtle way of telling the audience to “wait—there’s more.” The man stands on the threshold of death, but he does not cross it. This moment draws the viewer in, compelling us to lean closer to the screen. We instinctively want him to survive—after all, the film has only just begun. But Leyla doesn’t think the way we do. Although the man remains suspended on that border, for his daughter that boundary bursts like an overstretched vein. At this point, the director transports us into the past. The film’s palette shifts to black and white. Even as laughter echoes through these monochrome memories, we sense that something is about to happen…

In Amour, Haneke approaches a similar issue in a markedly different manner. At the commencement of the film, we are confronted with the lifeless body of the woman. The outcome is revealed in advance, and throughout the entire film, the director seeks to explain the the factors that lead to this outcome.

In the film Strange time, after the tragic incident that befalls the man, the girl discovers one of her father’s paintings among his works that she has never seen before. On the canvas, a human hand is depicted, and birds are circling around the open palm. This motif guides the viewer and sheds light on the film’s subsequent progression. The painting symbolizes the freezing of time. The depiction of the hand in this manner is the manifestation of an inner impulse. Perhaps it was an image emerging from the man’s subconscious that compelled him to create such a work. As the events progresses, the painting becomes identified with the character’s fate, or even predetermines it. Mehdiyev’s approach to the subject suggests that the source of the tragedy lies not outside, but within.

In Haneke’s Love, however, we observe the opposite. Here, an external intervention plays a main role. When George and Anna return home at night from a symphonic concert, they see an attempt to forcefully open the door of their house. Within the film, this appears as a very minor, seemingly insignificant detail. They do not pay much attention to it. Yet later, Anna’s illness and George’s dream remind us of this small detail. In George’s dream, he opens the door, steps into the hallway, proceeds along it, and ultimately is strangled from behind by an unknown person before waking up. This sequence suggests that the core of the film is structured around an external, unknown fear. The woman’s illness seems, in a way, to be the result of a “foreign touch”; here, the tragedy is presented as an intrusion into the body and life from the outside. Director Huseyn Mehdiyev situates a subconscious, metaphysical cause at the core of his film, while Haneke seeks to reveal the cause through physical nuances and external elements.

At the heart of Strange time lies the relationship between the father and his daughter. The father’s illness isolates the daughter from her profession, her love, and her social life. Initially, she perceives her care for him merely as an offspring responsibility. This dynamic is further complicated by her sense of guilt—had Leyla not called to her father from below while he was trying to catch the pigeon on the roof, he might not have fallen. The daughter’s obligation to her parent gradually imprisons her. She is forced to live a life of confinement.: she ceases her activities in the orchestra, distances herself from friends, and gradually withdraws into the home. In a scene during an orchestral rehearsal, where everyone falls silent and Leyla plays the violin alone in tears, it becomes evident that she is mourning her own fate, entirely alone.

We can draw a parallel between Leyla’s situation and the pigeons. The birds eat grain from her father’s palm, but when the man’s hand is tied, they are left helpless; this becomes a metaphor for the girl’s fate. The father’s hand is like the palm of time itself, and the girl is time trapped inside that palm. It is as if the father absorbs her time into his own being. As Leyla carries the responsibility of caring for her father, she gradually loses her sense of both time and space. The house turns into an enclosed area for her. Only when she opens the windows can she feel, even slightly, the breath of freedom. The reality of objects also melts within this deterioration: the girl puts the teacup on the table, yet repeats the same action again, as if time has become circular and objects have turned into imaginary forms she can no longer truly touch. All of this stems from the girl’s loss of the boundary between reality and illusion. Leyla, who once expressed her freedom through music, now finds the limits of her independence defined by the door between the living room she shares with her father and the rest of the house. For her, time does not flow forward; it repeats itself in a circular pattern.

In Haneke’s Love, however, the situation is structured differently. Here, Anna’s illness and her husband George’s care for her are central. Yet the man accepts this situation voluntarily. In this case, it is not compulsion but love and attachment that take precedence. George staying at home is shown not as a form of captivity, but as a deliberate choice. In Strange time, the house is a space where time has frozen and life has stopped. In Love, however, time begins to slow down as the lives of the characters unfold. Anna does not steal George’s time; rather, he deliberately spends his time on Anna. Because they are one. For them, time consists of the days they spend together. We can say: for George and Anna, time is memory. Memory manifests itself in the relationship between the elderly husband and wife. Their love has risen above daily care and physical concerns to a spiritual level, forming a deeper bond.

George’s recollections, Anna’s attentive listening to his stories, and the essence of their dialogues are beautifully revealed to the audience. We understand that the feeling that has bound them together and kept them side by side for many years is called love. George does not send the woman he loves to the hospital because he does not want to entrust her to strangers. This becomes clear when he pays the caregiver he hired to care for Anna and then dismisses her from the house. Because the caregiver hurts Anna while combing her hair. She does not understand the reason for the dismissal and even insults George. Yet a careful audience can clearly grasp what has happened.

Eva’s attitude toward her mother’s condition is different. In her closeness to her mother, it is clear that moral values have moved into the background. For the girl, her mother and father are not valuing but responsibilities. That is why she wants to place her mother in a hospital. She does not do this out of love. Eva wants to take this step because “proper behavior” seems to require it. Her way of looking at the situation has been shaped by the society she lives in. In other words, love here has already turned into duty and habit.

According to what we have discussed above, when we look at our own film from this angle, we see that, in fact, there is not much difference between Leyla and Eva. One simply grew up in an Azerbaijani environment, and the other in France. That is why Leyla’s moral duty—caring for her father—gradually turns into a burden that strips her of her freedom. She looks after her father not out of “love,” but because of an obligation imposed on her. We see her trying to convince the caregivers she hires to stay, but she never truly succeeds. Leyla lightly, almost playfully, scolds her father for offending the caregivers who try to feed him. This is where the contrast between George and Leyla becomes evident. The same sense of compulsion also scars her relationship with Orkhan. Here, love is portrayed not as a spiritual connection but almost as a promise of escape. Leyla hopes that Orkhan will come and rescue her from this “prison.” She reads the letters from her lover, writes replies, yet never sends them. We see a stack of unsent letters piled up in a drawer. This shows that her bond with the outside world has already been severed, and that she now lives solely within her own inner time. Writing, in this context, is no longer a means of communication—it becomes a form of talking to herself. In place of Orkhan, we constantly see the neighbor circling around her. His intentions are all too clear.

In the course of Amore, we also see neighbors who assist George. Their help is not unconditional—they offer a hand only in exchange for money. At this point, we realize that there is no essential difference between them and Leyla’s neighbor. George keeps them at a distance, whereas, despite all her struggles, Leyla’s neighbor, in the end, becomes the last glimmer of her dwindling hope.

In the film Love, both the man and the woman are musicians. At one time, their lives were shaped by music—that is, by rhythm and flow. Throughout the film, we see this music gradually fade away and turn into silence. This cessation is, in fact, a symbol of the decline of memory. The woman can no longer speak or move; she can only moan. Within this moaning, life itself is suffocated. The man, meanwhile, stays with her. He does not abandon her, does not leave the house, and leaves the world on the other side of the door.

For him, life is now connected solely to this woman—her breath and her suffering. The woman’s refusal to eat, her desire to sever her bond with life, becomes a source of immense pain for the man. Through her refusal, she decides to completely detach from life. The slap the man gives her is a manifestation of his helplessness. He does not want to lose his wife because he loves her, but he also does not want to keep her alive in such agony. Though he hesitates until the last moment, he ultimately strangles and kills his wife. Haneke does not present this scene as cruelty, nor as melodrama. He simply depicts it as the moment of death, transformed into the extreme limit of love. I think it is important to address a scene that follows this murder. The man catches a bird that has entered the house and holds it in his palm. He does not release the bird; he keeps it in his hands. This bird has now become the soul of his wife, yet he does not have the courage to set it free. In this sense, the bird becomes a symbol in the film of renouncing freedom and of turning love into pain.

The bird later seems to transform into Anna: awakens George, takes his hand, and together they step outside. We understand that, unlike Leyla, George has never sought hope in the outside world. The symbol of his hope has always been by his side. It is this “hope” alone that manages to lead him outdoors. Perhaps it is not George’s body that steps outside, but his spirit…

When Leyla tries to feed her father, the man behaves like Anna. The girl does not raise her hand against her father, because this is considered unacceptable in Caucasian society. Yet the anger inside her, the sense of imprisonment, and the feeling of being unable to be free suffocate her. She sinks into her father’s time and life. In this situation, we also see that the father experiences a moment of realization. He understands that he has become a burden to his daughter, and by attempting suicide, he wants to free both her and himself from this weight. But the daughter saves him, because for her this responsibility is no longer a choice but an act of surrender to fate.

At the end of the film, Leyla’s liberation occurs in a symbolic manner. The director returns the audience to a scene where time has stopped, where everything begins. The girl halts the clock on the wall, and time itself is suspended. The pigeons she nurtured, believing she ruled over them, are the very ones that led to her father’s death. By stopping the clock in the living room, the man’s power to command time is stripped from his hands. For a brief moment, his control passes into someone else’s hands. The “someone else” is revealed only when they step through the door. We understand that this figure represents the last glimmer of his dwindling hope. After her father’s death, the girl assumes his place, attempting to act as he did: opening and closing her hands, observing the birds. But now, she no longer wishes to set them free. This time, time itself rests in her palm.

After her father’s death, the daughter appears to return to reality, yet this return remains incomplete. She begins to play the violin again. Time begins to move once more, but one side of the clock remains stark white. For her, this represents a partial restoration of time, yet an irrevocable loss of memory.

Najaf Asgarzadeh