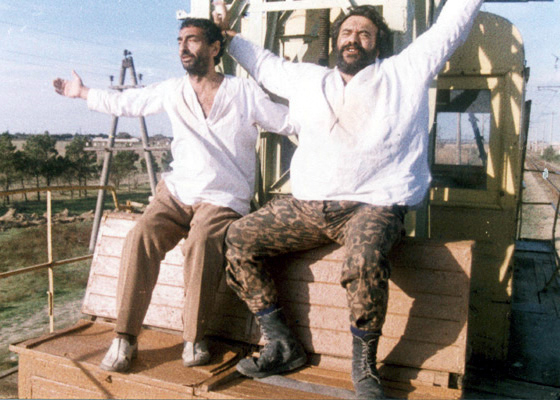

The Yellow Bride -We will win!

Back in 2005, during a broadcast on a Russian TV channel, Professor Kapitsa addressed the ominous subject of Europe’s unraveling. He expressed concern over the erosion of liberal values and the misconstrued notion of “freedom,” which he believed had led to the erosion of moral principles. Kapitsa’s words echoed the sentiment that Europe was undergoing a decline, not only as a system of values but also as a cultural entity.

Back in 1995, a decade before Kapitsa’s statements, Director Yavar Rzayev delved into this very topic, sharing his insights with the audience through the film “The Yellow Bride.” In one of the film’s episodes, Rzayev skillfully directs the viewer’s attention to a TV show. Here, the “host” played by the director himself engages his guest in a thought-provoking discussion centered around the “fall of Europe and its potential repercussions.” What adds an intriguing layer is the parallel context. While Kapitsa’s ideas were underlined by the Chechen conflict, Yavar Rzayev’s reflections found their backdrop in the Karabakh war. The overarching theme of the film, of course, revolves around the war, with the theater of events set in Karabakh.

Interestingly, in “The Yellow Bride,” the episode featuring the television program was tackled using a distinctive technique often seen in auteur cinema. The director shied away from conveying his viewpoint through his protagonist’s language, a move that would be somewhat incongruous with the cinematic approach. Instead, the filmmaker conveyed his musings employing the language of a TV presenter, marrying the medium’s nuances with his artistic expression.

The mood of the film is established right from the opening moments, primarily through its meticulous attention to detail in the description. Director Yavar Rzayev has a distinctive approach of collaborating with a new cinematographer for each of his films. During the film’s premiere, he proudly introduced the cinematographer Rovshan Guliyev as “the eyes behind my vision.” By working with various cinematographers, a director can effectively achieve the desired outcome for each project.

The film effectively serves as a profound exploration of the Azerbaijani mentality. The filmmaker delves into the intricate nuances, seeking to unravel the very essence of what war signifies for the Azerbaijani psychology and how an Azerbaijani man is expected to comport himself amidst conflict. Additionally, the film strolls the intricate interplay between women and war, delving into uncharted territories. A particularly remarkable visual culmination of Azerbaijani-war dynamics is found in the captivating sequence titled “Dance of Tanks.” Accompanied by resounding drum beats, this episode stands out as a pinnacle of strength within Azerbaijani cinema, leaving a lasting impact. Of notable interest is the fact that the director’s perception of authentic Azerbaijani mentality isn’t centered around the archetypal “heroic officer,” the protagonist of the tank dance. Instead, it’s the character Gadir, brought to life by Haji Ismayilov, who encapsulates the true essence of Azerbaijani mentality. Gadir, a seemingly fragile and vulnerable village artist, emerges as the embodiment of genuine Azerbaijani spirit, as envisioned by the director.

Gadir serves as a profound reflection of our mentality. A genuine Azerbaijani, he resolutely declines to embrace the role of a warrior and instead ardently advocates for peace. Our historical narrative strongly aligns with this sentiment. Gadir’s purpose in joining the war isn’t rooted in a desire for bloodshed, but rather in his quest to reestablish justice—a cardinal principle deeply ingrained in the Azerbaijani ethos. The profound significance of justice within the Azerbaijani mentality is undeniable. An Azerbaijani often values the principle of “justice” above mere legality, individual rights, and even religious adherence, such as honest practices-“halal”. In pursuit of justice—take, for instance, ensuring a child’s admission to an institute—an Azerbaijani might knowingly transgress laws (by offering bribes) and infringe on the concept of halal (by securing a student’s place), thereby compromising individual rights. This nuanced aspect is precisely embodied by the officer in Ramiz Novruzov’s portrayal. He unabashedly collaborates with an enemy officer to avenge his brother, even turning his weapon against his fellow soldier. Gadir, in contrast, firmly adheres to an unassailable concept of justice. To him, war itself is a profound injustice. In his endeavor to restore justice, the artist Gadir metaphorically exchanges his paintbrush for a weapon. Yet, crucially, Gadir refrains from trampling upon the principles of halal, human rights, and law in his pursuit of justice—distinctly setting him apart from the “average statistical Azerbaijani.”Gadir’s resolute protection of human rights, adherence to honest principles, and safeguarding of his artistic integrity—even at personal risk—sets him apart as a quintessential Azerbaijani. His unwavering commitment to these values exemplifies the authentic essence of being a true Azerbaijani.

“The Yellow Bride” stands as a film-manifesto, a cinematic proclamation where the director conscientiously adheres to the manifesto’s principles, surpassing mere professional requisites. The concern for the quality of composition had emerged in Azerbaijani cinema since the late 1970s. “The Yellow Bride” masterfully harkens back to the esteemed era of “Seyidzadeh, Seyidbayli,” (Azerbaijani directors) rekindling a level of quality reminiscent of that time. For the director, scale transcends being a mere technical concern; it evolves into a vital facet of artistic expression, a conduit for conveying the director’s creative vision. Noteworthy episodes, such as the “Shooting of the prisoner,” the “Bloody wedding,” and the evocative “Dance of the tanks,” are meticulously chosen, exhibiting a flawless mastery of scale in their execution.

Anti-cinematographic solution such as sacrificing image to music is often found in Azerbaijani cinema. The film “Yellow Bride” is selected with an ascetic musical solution. Director Yavar Rzayev and composer Sayavush Karimi managed to turn the folk song “The Yellow Bride” into a dramaturgical element of the film.

The film’s protagonists are familiar faces in Azerbaijani cinema, and tracing back through our cinematic history, we can readily identify their predecessors. Gadir finds his “film ancestor” in the central character of the movie “Birthday.” In the first film, Haji Ismayilov embodies the archetype of an “average” intellectual in a prosperous Azerbaijan (without any hint of irony), while in the second film, he represents an intellectual figure who has become disoriented by the ravages of war. Similarly, the “film ancestor” of the Azerbaijani officer portrayed by Ramiz Novruzov harkens back to another wartime officer – Hazi Aslanov. The composed and sagacious general from the mid-20th century conflict stands in stark contrast to the officer in the later century’s war, who appears more akin to a ruthless mercenary than a composed leader. This evolution of character depictions serves as a poignant testament to the erosion of moral values over the span of a century.

The film “The Yellow Bride” serves as an authentic document, offering a precise reflection of the initial years of the Karabakh conflict. The portrayal of the frontline village is characterized by a discernible scarcity: only a few panoramic shots, passive elders, and a bureaucratic official preoccupied with his office’s design affairs. Interestingly, the depiction on the cabinet’s wall, initially featuring “Red Square,” undergoes a transformation, now showcasing Koroghlu with a saz ( local musical instrument) in hand. This artistic alteration reveals author Gadir’s awareness of shifting political dynamics. However, an inadvertent mistake is apparent – a change from a sword to a sedge instrument, inadvertently symbolizing Gadir`s transformation from warrior to peacemaker. The village itself slumbers, emerging not as an active participant but as a victim of the war’s turmoil.

Throughout its history, Azerbaijani cinema has consistently embraced the theme of war, often portraying it as a crucible of trials that the protagonist ultimately conquers. Characters in films like “Babak,” “Fugitive Nabi,” and “I Loved You as Much as the World” have faced and overcome such challenges. However, “The Yellow Bride” deviates from this norm, presenting war as an aberration that unleashes untamed behavior within people. “The Yellow Bride,” serves as a seminal cornerstone, establishing the groundwork for the tradition of pacifist films within Azerbaijani cinema.

During the early 21st century, cultural theorists frequently engaged in discussions about the theory of the “new age,” a concept encompassing a fresh era, a novel generation, and an emerging wave of thought. The “new age” ideology comprises a set of values that transcend ethnic, religious, racial, and societal distinctions. As an example, this movement is evident in its music, where a synthesis of diverse national melodies converges with a harmonious blend of various religious motifs.

In the realm of cinema, the film “The Yellow Bride” stands as a creation firmly rooted in the principles of the “new age.” The truths conveyed by the creator surpass ethnic, religious, racial, and social boundaries. Furthermore, the folk song “The Yellow Bride- Sari Gelin” epitomizes a shared sentiment between two peoples, bridging their differing religions, languages, and cultural norms. Particularly noteworthy is the pivotal scene of “Meeting Malacan,” where a Gregorian Armenian and a Muslim Azerbaijani seek refuge and solace within the abode of a Malakan Russian. Despite the Malakan sect’s Christian affiliation, its distinct “Sufi” monotheism shines as a beacon of the “new age” ethos, embodied by the venerable old Malakan character.

For him, the soldiers on both sides of the war are all children of the same God, yet one of these parties seems to have lost their way (or perhaps both have). Even the Malakan character, despite being an ethnic Russian, carries a sense of guilt within. Within this scene, the author employs symbols and framing to offer an interpretation of the role the Soviet empire played in the Karabakh conflict. In this film, the alter-ego of the author isn’t Gadir, but rather the elderly Malakan man. Yavar Rzayev, in his portrayal of the Karabakh war, doesn’t seek to convey an “Azerbaijani” or “Armenian” truth, but rather a truth that transcends such distinctions – a truth of divine essence. The fact that the representative of a nation that endured the sacrifice of countless martyrs and 20% occupation of its territory was able to find the strength within to create this film, speaks volumes. This courageous step could only have been taken by a people confident in their impending victory, even while the war was ongoing.

The summer of 1991. After discussing all the pleasures of the world, a group of students of the film directing faculty of the Institute of Arts devote two minutes to the subject of Karabakh: “Can you imagine, Armenians occupy Baku.” (He laughs with irony) “But they should walk over my dead body for occupying” – he answers.

The summer of 1992. Barber: “How will this war end?” he complains. Customer: “Do you have doubts? We will be in Stepanakert/ Khankendi in two weeks.”

The summer of 1993. The former resident of Sovetski Street, after visiting all the nearby shops in search of bread, sees his acquaintance and stops: “Aghdam has gone too…” He takes a couple of puffs from his cigarette: “Gubadli, Jabrayil will also go… I’ll go and see where I can find bread.”

The year of 1998. The premiere of the movie “The Yellow Bride”. I am leaving the hall. The Karabakh war… Personal problems… Hopelessness… “The Yellow Bride” movie: We will definitely win!

The article was first published in “Kino +” newspaper in 2005.

Ali Isa Jabbarov