Teymur Daimi: “Cinema is not art but transcends its limitations.”

Our interviewee is the philosopher, painter, and film director Teymur Daimi. In this conversation, we have touched upon the themes dealing with the theoretical framework of our cinema and the role of experimental approaches in its development.

– Mr. Teymur, what drags you to particularly experimental cinema?

– Reply is so ordinary. I came to cinema from painting and visual arts. To my opinion, it is natural process. I have never desired to become a film director. I was not a cinephile by any means but I was engaging in painting for a while. Later I came to realize that painting alone could no longer fully express my desires. My works were being acknowledged — some praised it, others critiqued it — but there was always a missing piece from the puzzle. I could not figure out the incompleteness.

– Wasn’t a movement missed?

– This understanding came to me after a certain period of journey. Then I started to involve in performances, installations and contemporary arts. But even, something was lacking. In 2001, Strasbourg hosted a large-scale photo and video art festival with participation of Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia. Curator of the festival encouraged me to perform an experiment with video art. He offered me to take a camera to make an effort. I was excited with the offer because this was a completely new field for me. I grabbed a VHS camera and shot a short experimental film “Under Cover”. Despite being rather primitive, this is my favourite film up to this point. While filming “Under Cover”, I found out that this was exactly what I had been searching for. Movement and sound were edited there. Perhaps tomorrow I’ll include dialogue in my work. This is an experimental film. Much of the inspirations in classical and traditional films are rooted in literature. That’s not my cup of tea. Visuals and sounds are the core of my interest. You could say that I’m carrying on with painting. Therefore, I shifted effortlessly from painting and dyeing to experimental cinema. By the way, the painters, as Fernand Léger, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, made the earliest experimental films. To be honest, I dislike the terms “experimental and video-art.” In my opinion, film stands somewhere between visual art and cinema. It is neither conventional cinema nor painting. Roughly speaking, this is a hybrid form. To my mind, I am capable of entirely conveying my ideas to the viewer referring to this medium.

– Surrealists, expressionists, avant-gardist all experienced this technique. For what reason do we refer to this style as experimental? In many film festivals, there is also a separate “experimental cinema” category. When the term “experimental” is applied, seemingly it is no longer recognized as a full-fledged cinema.

– No, the experimental cinema possesses its own distinct stratum and auditory, with film directors like Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren holding a distinctive position in film history. Ultimately, we will observe their radical difference when comparing experimental cinema with conventional cinema. In fact, it is an experiment. I shoot something — maybe it succeeds, or maybe it fails. For this because we call as experiment. Once, film director Mirbala Salimli told me that if you make a major film, you cannot make mistakes. However, a director produces an experimental cinema can make mistakes. Comparing a major film, it is much freer.

– They won’t notice the mistake?

– No, they will notice. But this mistake might be deemed as the author’s visual stylistic fingerprint. Suppose I’m working on a piece, suddenly I interrupt the visual continuity or transform the image. Directors working in the classical style would consider it as a mistake — even a kind of “ridicule or mockery.” They don’t accept such mistakes. But in experimental cinema, such “mistakes” are fairly common and are frequently welcomed as stylistic language.

– In undertaking such gestures, do you have a predetermined specific purpose in advance? Do you know what you intend to attain?

– It may happen accidentally. But I do intentionally. For instance, let’s consider the film “This is love”. I could have shot it using a professional-grade camera.” However, I assumed that high-definition cinematography would not capture the ambiance or mood. Therefore, I opted for a phone recording. The camera has rudimentary optics, I loved how it framed reality — the footage resembled still-life painting. Eye-perceptible pixels become a central component of the visual style. I have done it deliberately. High-resolution visuals don’t appeal to me; I am not fond of it. To my mind, it is glamorous. I can’t watch most Hollywood cinema — even many art-house productions strike me as artificial. If I had shot those films, I would have purposefully corrupted the image resolution.

– In the interview recorded in the 1960s, Bertolucci stated that “I believed that style and technique would drive cinema’s evolution. However, it’s become clear to me that this isn’t true. Perhaps, cinema’s progress will come from discovering new storytelling structures.” From today’s perspective, what is cinema’s true dilemma — style, auteur technique or narrative forms?

– Generally, cinema is in a constant state of evolution at every step. According to Oleg Aronson, the Russian art theorist and philosopher, it is impossible to theorize the cinema because you write something today, and the next day cinema has already moved beyond it. Cinema avoids the frame you defined, and always renews itself. Cinema prevails over theory. It is a kind of medium and consistently transforms itself. When we speak of cinema, we often mean classical cinema. What does cinema really mean? Moving images. So, in fact, you can include many things within cinema — video games, digital items – all of these belong to cinematic condition. For that reason, the field of cinema seems to be expanding, evolving. It is beyond the questions with style, script, or other such problems because cinema is vast, expansive, and has no fixed borders. Let’s assume that I am a viewer. I can watch film that intimates and is comprehensible to me. No one compels me watch films out of my choice. Occasionally, directors and critics express their dissatisfaction over the omission of certain elements; they insist on making a shot on alternative themes. This is precisely what a director should film. Tarkovsky couldn’t have made genre films — it is pointless to critize him. In a sense, everyone walks at his own pace and finds his own rhythm. That’s exactly why, as a viewer, I’m free to choose whatever film I desire — the options are abundant. So, saying that cinema is currently experiencing difficulties… Many things – almost everything – are becoming younger and moving in a positive direction, both technically and narratively. That is why, from my point of view, I don’t see any trouble, it lies in administrative obstacles. Someone strives but several external barriers appear, the process is blocked, and failure occurs. I consider it as a trouble. Cinema, by its very nature, is not in trouble; it is progressing.

– During one of your speeches, you characterized that determining whether any work is classified as a piece of art and evaluating it on that basis is a feature of capitalism. Then what is art? What qualifies as art, and does not? To what extent is this statement true: “this is art” or “this is not art”?

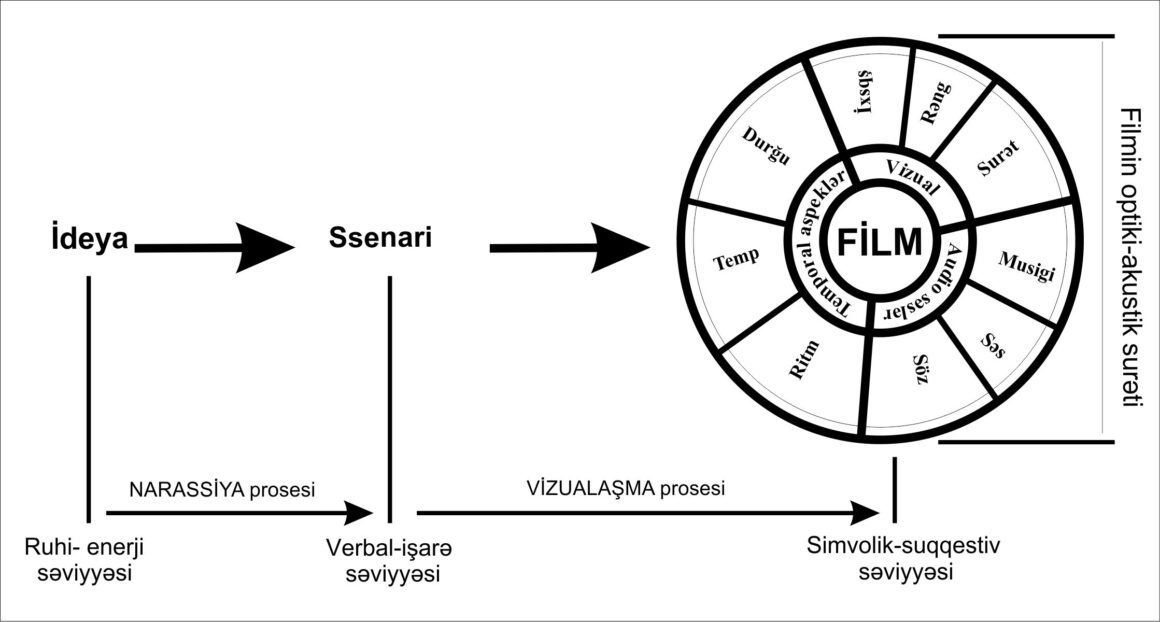

Cinema – is neither art nor fine art. We artificially project the notion of art onto cinema from outside. Film directors – like Tarkovsky – those we classify as art-house auteurs routinely claim that they are making art house movies or engaging in art. But that’s not entirely accurate because cinema, since its inception, was positioned between science and entertainment. Science stands on one side – it possible to investigate scientifically intriguing subjects using cinema as a medium.” On the other side, cinema is a medium of entertainment. There’s a heavy sense of pathos in the word ‘art’. When I claim my engagement in art, it turns me into a kind of snob and I hold myself in higher esteem than others. I swear and criticize everyone. One thought refutes the other. The core of cinema is not art, but other concerns. Currently, even the essence of the cinema is unclear to us. We are still studying. When we discuss on art, we regard cinema as an extension and a branch of the fine arts – visual arts. But it is not as we consider. This is a technical entity, product, and embodies a broad and tremendous powerful capacity. Even philosophers, particularly those like Gilles Deleuze, explore this phenomenon. Cinema functions through our consciousness and comprehension. The subject of my sixth book will be cinema. I desire to invent my theory relating with cinema and to make researches. I will try regardless of being failure or success. Cinema serves as a tool for shaping viewer’s perception, consciousness and self-awareness. Even it transcends the limitations of art. When I remark that cinema is not art, it does not imply we are undervaluing it. No, art is artificial. We define something as ‘art’ and then begin to worship it. This is called idolatry. Cinema goes further; it is a kind of therapeutic means, event deeply spiritual force but not in primitive sense. Cinema is extremely terrifying. In some cases, when I say ‘this is not art’, people assume it as low or primitive, if it’s not considered as “high art”. Contrarily, art has not yet reached the level of cinema. We have created art by artificial means. We claim that something is art; if it is so, it is valuable. At the second phase, we make discourse of market value. This is, by its nature, capitalism. This inherently devalues art. When someone claims that “art is worthless”, it means that art is exceedingly costly. You are already rendering it into a product of capitalism and monetary relations. Shortly before, art, in its turn, is an adequate word. As a matter of historical background, there was not such a concept like the word “fine art”, “art”. This word, in the meaning we use nowadays, dates back to the 15th century during the Renaissance. I have also scripted about this matter in my book. Art existed in ancient times, but it as a name “techne” (techno – in the present). In other word, art is a technology aimed at altering or modifying something. The concept of “art” emerged in the Renaissance period. Over the past 500 years, we have become captives of this word. Art emerged from religion and has itself become a kind of religion. Museums are contemporary temples. We go to the museum as if we were visiting a temple. This is idolatry. As a result, while discussing art, we should not declare that it is something exalted; rather, we should describe it as something bad. In this context, I have mentioned Tarkovsky — now they’ll want to kill me.

– You stated that the cinema has no troubles.

– For itself. Film directors have enough on their plates.

– Apart from administrative obstacles, what constitutes the core problem if Azerbaijani cinema with respect to creativity? Screenplay, story, directing…

– One of my articles I authored for “Fokus” magazine was titled “Has Cinema Ever Truly Existed”. Screenplay was generally unimportant, as I wrote in the article. Indeed, Hitchcock used to say that the first most vital element in a film is the script, the second element is the script and third one is the script. This is how conventional film directors should talk, I understand them. But this is not the major point. Seemingly, Chekhov said that if you are searching for a subject, you may write about even a teacup in a way that it becomes a worldly drama that enthrals you. Actually, it is actually impossible to go beyond the framework of the 36 dramatic situations. To my mind, bringing innovation here is not only challenging, but impossible. Screenplay in classical-style films, specially produced by Hollywood, is indeed crucial. Art-house cinema, to some extent, is also a form of conventional cinema where a screenplay can still hold significant. However, this is primarily related to the director’s decision. As a sample, for Apichatpong Weerasethakul, concept is more important than the screenplay: concept and originality. He films extraordinary subjects in an unconventional style. Style is essential. And above all, cinematic language! You see, I’ve identified the core issue. This is neither a script nor another. Cinematic language!

– Do you believe that movies no longer speak every language?

That is true, it seems that everything has already missioned. So how will you impact on the audience? But in experimental cinema, really you have opportunity to make original, extraordinary film. As a result, experimental film has attracted a lot of attention at international film festivals and in the world of film in recent years. In previous decades, conventional movies received less attention because viewers have already been tired of conventional cinema, they are seeking something new. However, this can only be accomplished with the contributions of other fields, such as science, visual art, and perhaps philosophy. That is reason such matters are taken into considerations. The priority given to script and dramaturgy stems from a literary perspective. However, I tend to avoid it and try to do it because I was shaped by painting. I approach cinema from another angle. Imagery and sound are important for me. As a matter of fact, this is just cinematic language. Directors cowork with the screenplay and actors. Such elements are on their focus. Screen and imagery avoid the spotlight. However, this is the key issue. To this respect, the most of serious directors, auteurs – such as Peter Greenaway or David Lynch — create their films using visual-centric aesthetics. Incidentally, David Lynch graduated from an art college, whereas Peter Greenaway was trained as both an architect and a painter. Lynch initially shot video art movies, then shifted toward traditional cinema. Even within the framework of traditional cinema, he had always made experimental films. The films “Mulholand drive” and “Inland Empire” are completely experimental. Godard’s most recent films are characterized by their experimental natures. But classic, conventional film directors and critics criticized him in time. Godard said that he had long aspired to and ultimately succeeded in accomplishing. He stated that he would be happy if I could also create in the same way.

– Mr Teymur, if we look at Azerbaijani cinema today, particularly in the aftermath of the war, the discourse around nationality and national identity has become increasingly topical. What is national cinema, and how should it function? When we cite that Azerbaijani directors struggle to find their own distinctive cinematic language, one of the key reasons is related to the unresolved issue of national identity. But is that truly the root of the reason?

– As Lenin famously stated, cinema is the best means of propaganda. From Eisenstein’s era on, cinema has always become a component of propaganda. Ideologues recognise that cinema is a highly influential medium. We can infuse such ideas into society through cinema. I take no mean when directors themselves strive to make propaganda. Because a director should consider entirely different aspects. They should think about cinematic language, be involved just with cinema itself, not with ideology.

– Generally, does the concept of national cinema exist for you? Or let me express differently: what does this imply to you personally?

This is artificial intellect. For example, when speaking of contemporary visual art, the artist’s origin has no essence. Artist’s character and works are considered. Artist’s creativity and personality are meritedly assessed. As it happens, cinema has a history; the concept of national cinematography exists as a distinct segment. Therefore, this subject is inevitably discussed. A director must begin by questioning themselves: what does he aim to do, what is essential to me? If highlighting the national segment or the factor of nationality in his creative work is vital for him, accordingly, he is free to do it. But, you cannot force all directors, painters, and artists the notion that they must all think exclusively about national art. It is entirely voluntary. I mean, there are people who do it. Admittedly, I find it difficult to grasp what they do. Because when ideology enters the conversation, the work becomes an instrument of propaganda. When one of our directors presents a film at international festivals like Cannes, critics may name it as “national, Azerbaijani film.” Actually, they discourse about film and its director. Because the plot, fabula reflected in the film resonate with people from any country and express universality. This is the most essential. When a director presents his film as Azerbaijani national identity, it means that this is not his voice or speech. This speech is almost a cliché. When an artist speaks on behalf of nation or people, he loses his temper and becomes a mouthpiece of nation. This is, somehow, universal cliché – a national propagandist cliché. For this cause, it is not appraised. By the way, when I write about the short feature film “Salt, Pepper to Taste” directed by Teymur Hajiyev, I have touched upon the theme of speech clichés in cinematic discourse. In Teymur’s film, he visually doesn’t present the character. This because once the speaker is shown, the utterance no longer belongs to that person. Speaker is not truly himself. Someone makes a statement through another’s mouthpiece. Consequently, the speaker’s visual presence is intentionally unrevealed.

– Mr. Teymur, you stated that cinema has always presided over one step of theory. Well, is the existence of theory necessary or not?

– No, theory is necessary and must be. I consider that director or philosopher like Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov and Godard can develop the most profound theory. In other sense, a director should develop his own theory as well. These directors’ experiences are therefore interesting. If you approach the film as a theorist, things become somewhat more difficult. He gets engaged with other activities and directors fail to understand his words and actions.

– Gilles Deleuze is a good example…

Deleuze, as a philosopher, developed an impactful theory and is a cinephile as well. He has watched an excessive number of films. Most directors have difficulty comprehending his theory. Because he has delved into theory. Eisenstein would absolutely have understood him, and Godard undoubtedly did. However, some fail to catch his ideas. A director must also be a philosopher in order to understand. Theory is extremely essential. Even if a director aims at attaining something, makes a film with deep meaning, he must be a philosopher at any rate. He may not write philosophically but he must contemplate. Directors like Coppola, Kubrick, Greenaway and Lynch have achieved in writing philosophical text. All of them are, to some extent, philosophers. Tarkovsky was also a philosopher. Godard is, undeniably, a philosopher. Those who have no interest in theory, who do not think, inevitably become illustrators; they just illustrate a script and put on screen. Consequently, his films suffer from being surface-level, devoid of cinematic depth. Theory plays a substantial role in cinema. Therefore, I engage in theory because this pushes me onward. Idea or concept always precedes the final product. If there is lack of concept, experience will cease and the author creator will stagnate at a certain stage or be exposed to creative repetition.

– In your opinion, have the cinema theories played notable role or occupied a distinct place in Azerbaijani film culture?

– To my mind, it will happen. I anticipate. The theory is given significant importance at educational institutions in foreign countries. Certainly, this will absolutely be reflected in the films shot by young film directors studied there.

– Hasn’t it already happened?

– It is hardly possible to find. It’s challenging for me to identify the director who approaches a film being infused with philosophical thought.

– Can we give an example of Hilal Baydarov?

He has a wonderful inborn talent. In my perspective, if he doesn’t study philosophy, cinema theories, he will incur repetition in creativity. Alternatively, after making several films, his cinematic creativity stagnates. If young film directors focus on theories, philosophy, they will fall into repetition and make films blindly. Theory functions as an operative power and plays a significant role in practice. Therefore, great directors are simply philosophers. An idea should be prompt. I don’t like this expression. Undoubtedly, if there are no ideas, everything will stagnate and decline. The fact of the matter is that this is not our directors’ fault, but rather their misfortune. Most of them are influenced by theatre and theatricality. They are mainly concerned and work with plot, actors, and dramaturgy, while sparing comparatively little time to cinematic language. What is cinematic language? To my mind, cinematic language encompasses the concepts of editing, temporality, and audiovisual elements. Cinematic language is derived from idea, and is the core of cinematic thoughts. An individual who uncovers a new cinematic language leaves a lasting mark on the history of film. As an example, I can cite Sokurov. His films represent a new sign, a new letter in the history of film philosophy. This is the reason his films are considered original. Sokurov is constantly evolving, being in a state of transformation. His recent film is purely an experimental film and directed by using AI (artificial intellect) tool. From my perspective, the so-called film should be represented as a cinema installation in an exhibition hall rather than displayed in movie theatre. Because it is hybrid. Broadly, I like Sokurov’s directed movies. In my opinion, he is happy. Although not being regarded as an experimental filmmaker, he always makes experimental films. He always talks about different things. For instance, he stresses the importance of literature. But, what he says differ from what he actually does. Actually, he explores cinematic language. Speaking of this matter, in the last two or three decades, it seems I have watched two experimental explorations on cinematic language in Azerbaijani film: “The Bat” directed by Ayaz Salayev, and Teymur Hajiyev’s entire filmography. Apparently, the main problem of Azerbaijani cinema is… The statement might offend some people, so I’m not sure whether to say it or not.

– I will give my next question until taking a moment to think. We have started our conversation about an experimental film. Currently, no one has been engaging with this direction. I might hardly give examples. Does experimental cinema contribute to the emergence or the delayed development of a new cinematic language? In fact, experimental cinema served as a fertiliser of the world cinema – movements such as Surrealism, Expressionism and others were later nourished.

– Exactly. First of all, this is the source of everything. Therefore, an experimental cinema is highly praised in the West. Certain methods originated in experimental context, are tested and integrated into traditional cinema. Why does it occur initially there? This is because producers cannot allocate funds to these experiments. Failure of these experiments could mean defeat for them. As a result, innovations are first tested in experimental cinema, and then conventional directors incorporate them into their films. Accordingly, experimental cinema must exist. Cinematic language does not evolve or exist in its absence. There is simply a desire to illustrate literary-derived ideas as in our cinema. That is exactly what I meant to say before. I was wondering if I should tell you. The primary issue with Azerbaijani cinema is that it is in the phase of illustrating literary ideas. Naturally, I speak purely based on my personal experience, and all directors cannot be included.

– This is an interesting idea. Because the estrangement of our cinema from literature is frequently discoursed as a negative factor.

To assert that cinema has estranged from literature… Screenplay, even the worst screenplay, is fundamentally a literary work. Director becomes its illustrator of the screenplay. He is neither an author nor a person creating new audiovisual product. He becomes only a secondary figure and continuously makes “the cut-paste” operation in his directing creativity, that’s all. It is impossible otherwise. In contrary, our directors will keep doing the same thing they’ve always done: classic film, traditional storytelling, fabula, protagonist, and so on. Perhaps, everything will be perfect. However, this will not signify progress. All of these have occurred repeatedly and rooted in the 20th century. It is high time to do something else, such as conduct experiments. It is absolutely necessary to expand the experimental sector and support the young directors dedicated to this field, so that something genuinely related to cinematic language can emerge there, enabling conventional directors to utilize them. It is not feasible otherwise. Cinematic language cannot evolve differently. It will constantly serve as illustration.

Interviewed and texted by Aygun Aslanli