R. Ibragimbekov: “Cinema should be like the sea”

It appears to me that, much like the way we naturally develop a language for communication, the language of cinema emerges intuitively within an individual. Understanding its full potential often comes after one begins to utilize it. As time progresses, various superfluous elements and influences from other art forms tend to be discarded, resulting in a purification and refinement of the cinematic language throughout the creative process. However, it’s also not uncommon for individuals who possess an innate purity in the language of film to introduce deliberate, rational adjustments. Paradoxically, such well-intentioned modifications can sometimes lead to the contamination of this natural cinematic language.

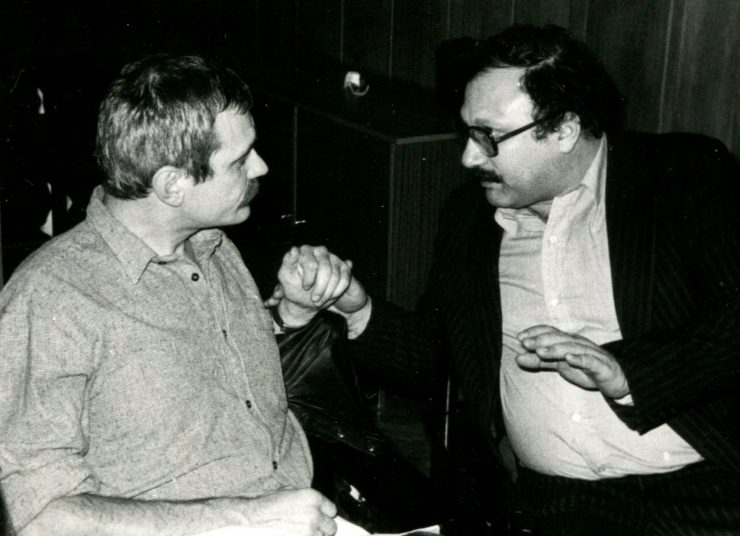

At times, the language forms of other arts, such as theater, can closely align with the language of cinema. However, in cinema, the incorporation of borrowed elements, like citations, is permissible only when they seamlessly integrate into the film’s visual structure. The figurative system and language of a film are typically crafted during the scriptwriting process, but their actual realization can vary greatly under different directors’ interpretations. For instance, in our collaboration with Rasim Ojagov, who I’ve had the privilege of working with on several films, he possesses a keen understanding of the essence of my scripts. This connection is incredibly valuable to me because, as someone from a different professional background, finding an individual who truly comprehends and shares the same sensibilities can be quite challenging. Sometimes, even if a person aligns with you in terms of mood, other aspects like differing senses of humor can hinder the creative connection. Therefore, it’s essential to identify a multitude of compatible traits in order to effectively collaborate with someone. It’s akin to tissue matching, where numerous factors must align to ensure a successful partnership, as there are many potential rejection factors to consider.

Ojagov is someone who shares a remarkably similar perspective with me, from his life experiences to his creative sensibilities. However, he inherently leans towards cinematic simplicity, and my attempts to steer him away from straightforward narratives prove to be quite challenging. Even when we agree on a particular direction, he seems to be bound by an intrinsic conditionality, as if compelled by some inner force. This very resistance, oddly enough, is a testament to his true artistic nature. There’s an unconscious tendency within him to drift, to diverge from the conventional. Yet, he struggles to consciously alter his artistic framework. The outcome of this struggle is a well-defined and fairly steadfast lexicon. This stabilized artistic framework gives rise to a cinematic language that is inextricably linked to it – characterized by its simplicity, brevity, and unmistakable clarity. Interestingly, this aligns quite closely with my own writing style.

I also prefer simplicity in my writing. However, when Ojagov and I attempt to construct something structurally ambiguous using these seemingly “simple” building blocks, we often find that the result becomes more locally intricate than we initially envisioned. I don’t like overly complex language in works. Nature, after all, operates in layers, and I believe that creative works should reflect this multifaceted quality. It’s about transitioning from one straightforward layer to another, gradually building a perceptual complexity that becomes apparent to a sufficiently discerning audience. I firmly believe that films should not be critiqued solely from the standpoint of a highly intellectual audience. Instead, the understanding of a film should unfold step by step, layer by layer. When catering to an audience with varying levels of intellectual preparation, a film should be designed not just for the intellectual leaders but for everyone in the spectrum. I’ve made a similar comparison before, but it’s worth reiterating.

Just as in the sea, where everyone should have the opportunity to explore to their heart’s content, the world of living matter follows a similar pattern. A weak swimmer may find joy in floating near the shore, while a strong swimmer can venture into the depths. Similarly, the intricacies of biological tissues remain hidden until one delves inside, much like how a single-eyed observer might perceive them as straightforward. However, for a more seasoned individual equipped with a scalpel and a microscope, the boundless complexity of cellular-level matter unfolds before them, revealing a world of intricate wonder.

In my writing, I never shy away from the vast realm of complexity. Each time, I pour my heart and soul into my work. Moreover, it’s entirely possible that what appears as a boundless sea to me might be nothing more than a modest lake to a towering observer, beyond their reach. Nonetheless, I firmly believe that even intricate figurative systems can be conveyed in simple language. This notion of mine is deeply intertwined with my nature, evident both in my life and my writing. It seems only fitting, as language is a reflection of one’s essence, a channel for the author’s fundamental inner traits. In this sense, it takes shape under the influence of the image system while simultaneously shaping it in return.

As someone deeply involved in both literature and theater, a central aspect of film language and its figurative system holds paramount significance for me. The visual elements, language, and their boundaries in cinema, much like in other art forms, are fundamentally shaped by the essence of film itself, which is unveiled in its relationship with the world it mirrors. When discussing the core essence of any art form, it appears crucial to consider how that art form relates to real life. Among all artistic mediums, cinema stands out as the one closest to life, thanks to its unique mode of reflection. This distinct characteristic sets its aesthetics apart, even from the aesthetics of television, despite their shared technical capabilities. In the comparison of these closely linked art forms, it’s the criterion of their connection to real life that enables me to draw a clear distinction between the aesthetics of television and those of cinema. In each of its creations, cinema maintains a balance between extreme wide and extreme close-up shots, akin to the capacities of natural human perception.

Even when a film unfolds within the confines of a single room, where the camera’s perspective predominantly dwells within that space, it remains crucial for the camera to capture zoomed-in details. This ensures that the balance between wide-angle shots and close-ups is maintained, mirroring the way we naturally perceive life. This requirement aligns with our innate visual capacity, honed and validated through the realm of fine art.

Take, for instance, the Japanese film “Woman in the Dunes”, where the entire narrative unfolds within a sandy soil. Despite this confined setting, the film manages to convey a rich sense of life’s fullness by ensuring that the camera not only captures the people but also meticulously observes everything that exists within these unique circumstances, right down to the behavior of ants.

Television cinema, on the other hand, may often have a narrower balance between establishing and close shots. Throughout such productions, the predominant focus can remain on wide and medium shots. However, this doesn’t detract from the viewer’s sense of a complete reflection of life. In this medium, there’s a remarkable penchant for verbosity, a literary quality, and an increased reliance on the power of dialogue. In essence, in a purely quantitative sense, a significant increase appears in television cinema.

I’m often asked why I craft narratives differently for the cinema and the theater. This decision primarily hinges on the raw material of life that serves as the foundation for each of my works. My foremost aim is to achieve the most vivid and expressive representation of this material. Consequently, I find that both the genre and the language of the work must align with the essence of what I wish to convey at a given moment. While the significance of language and the figurative system cannot be underestimated, they ultimately emerge as a response to the nature of the subject I wish to explore. It’s only then that the process of communication truly begins, with language and the system of imagery shaping and refining the initial messages. This dynamic involves a two-way process of refinement and adjustment.

To me, the theater represents an opportunity to embrace conventionality, symbols, and the deliberate deformation of life’s material in order to achieve a multi-layered and profound outcome. While I do appreciate hyper-realistic and naturalistic theater, I can’t help but feel that this approach sometimes limits the theater’s inherent potential and starts to encroach upon the territory traditionally associated with cinema. If we delve into the core distinction between these two art forms, it becomes evident that theatricality primarily thrives on the rejection of a literal replication of life. Instead, it strives for a more abstract and meaningful representation of life’s essence on the stage. While cinema often aims for a faithful replication of reality, theater stands apart by emphasizing a figurative, symbolic, and thought-provoking portrayal of life’s complexities. All attempts to not reflect life in the cinema in its own forms, with rare exceptions, do not achieve artistic credibility. I recall the film “Allonsanfan” by the Taviani brothers, where, as the story unfolded, certain conventional, almost theatrical elements gradually interwove themselves into the fabric of the otherwise realistic narrative. These elements, however, felt so seamlessly integrated into the chosen visual and thematic framework that they became an accepted part of the storytelling. For instance, Marcello Mastroianni’s character in the film sported makeup on his face, and he openly removed it during a pivotal moment. This seemingly theatrical gesture, so intimately tied to the character’s inner essence, served to heighten the emotional impact of the actor’s performance on the audience. Such instances are quite few in cinema.

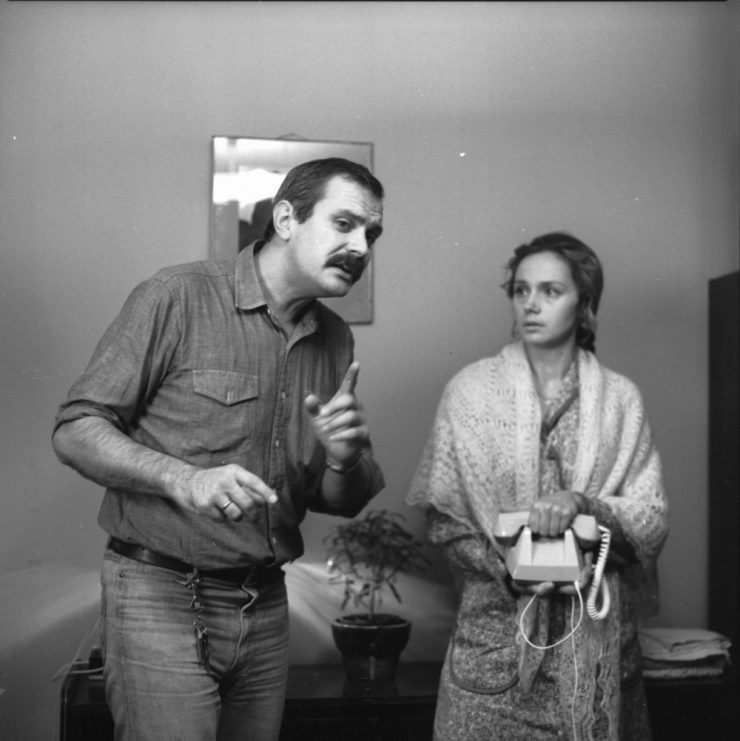

In my view, Nikita Mikhalkov’s film “Without witness” represents a deliberate departure from the conventional image system. Upon viewing it, I arrived at a somewhat unexpected conclusion: when one consistently pursues complexity and refinement in artistic language, there’s a distinct tendency to ultimately arrive at a form of simplicity or even primitiveness. A parallel can be drawn in the world of fashion as well. Through the gradual pursuit of perfection and refinement, fashion has at times reached a point where it borders on kitsch, embracing programmed tastelessness and challenging traditional notions of aesthetic harmony. Now, turning to the film “Without a Witness” it exhibits two particularly interesting features. The first approach aims to directly engage with the film’s audience, a practice rooted in the theatrical tradition. This connection is established by having the characters address the viewer, similar to how actors in theater often break the fourth wall. The second approach involves forsaking intricate psychological nuances and diverse character development. In the film, the essence of the main character is portrayed with utmost clarity, almost as if the entire array of psychological intricacies has been set aside. The entire narrative revolves around a rediscovery of the protagonist’s initial state, essentially a return to where they began, contrasting who they were with who they have become. Consequently, the character’s complexity is laid bare through this juxtaposition of their two states: who they once were and who they’ve evolved into. In effect, this approach creates a novel figurative framework within N. Mikhalkov’s cinematic repertoire.

It’s worth acknowledging that the initial attempts by the characters to directly engage with the audience somewhat disrupted my immersion in the story, and this feeling persisted until near the conclusion. There was a noticeable disconnect between me and the unfolding events on the screen. However, as the narrative comes to an end, I gradually embraced this figurative approach. It appears that in cinema, any strong method of direct audience engagement requires a form of “camouflage.” It can certainly exist but needs to be introduced thoughtfully to draw the audience closer and prepare them for such moments. To a certain extent, the appeal to the audience has always been present in cinema. This connection is often forged through the art of montage, employing counterpoint: at times, our perspective aligns with one character’s viewpoint, and at another times, with another’s, yet both of these perspectives effectively reach out to us as viewers.

The most significant achievement of filmmakers during the 1960s and 1970s was the profound expansion of their cinematic language tools. This advancement allowed for a more profound exploration of the human psyche, enabling filmmakers to delve into the subtlest movements of a person’s heart and mind. In this context, it’s worth noting that Federico Fellini’s “8½” marked a pivotal moment. During its release, many found its cinematic language to be intricate and somewhat challenging to grasp. However, over time, Fellini’s entire toolkit of cinematic expression has been so thoroughly mastered that it now feels almost commonplace, as if it has become an essential part of the cinematic canon.

Certainly, directors have traditionally held a pivotal role in shaping the language of film, and this remains true to this day. While exceptional playwrights and cinematographers, like Urusevsky in his time, have made significant contributions, it’s often directors with a strong authorial voice who wield the greatest influence over the film’s language. This is because the script serves as their primary canvas for self-expression. To draw a parallel, one might liken this hierarchy of influence to the concept of trophic levels found in ecosystems, which categorize all living organisms based on their method of harnessing solar energy. In this analogy, the first trophic level represents plants, which directly capture solar energy. The second level comprises animals that derive their sustenance from plants, indirectly tapping into that solar energy. Lastly, the third trophic level corresponds to humans, who consume both herbivores and carnivores, effectively accessing solar energy through this intricate food chain.

When it comes to their outlook on life, the dramatist can be likened to the first trophic level. They are akin to plants, drawing directly from their own life experiences and inspirations to create their works. The director, on the other hand, operates at the second trophic level. They build upon the dramatist’s foundation, taking the playwright’s words as a starting point, which have already been shaped, refined, and transformed by the playwright’s perspective. However, just as different life experiences lead one playwright to craft one type of work and another to create something entirely distinct, the same script, even if only subtly, can be approached differently by various directors. In this dynamic, the language of the future film finds its distinct form. This occurs because the director, melding the provided literary material with their own artistic desires and personal experiences, discovers a more vivid and figurative cinematic expression for it.

I’d like to delve into an intriguing facet of modern film art – the musical genre. At times, these musicals are built upon existing works of art, ones that we already have well-established notions about in terms of their figurative structure and language. Yet, when they transition into a different stylistic system and adopt an alternative language, they acquire a new dimension of quality and power. Take, for instance, a film like “Oliver.” It’s based on Dickens’ literary masterpiece, a work that most of us have read and that epitomizes the classic prose genre. In the cinematic adaptation, music takes on significant dramaturgical roles, assuming emotional and meaningful functions. A genuine musical stands apart from a standard film with supplementary music; here, music becomes a profound narrative element. Through this transformation, a musical finds a unique musical equivalent for what would typically be conveyed through words and actions in a conventional film. As a result, by replacing the traditional expressive language with the musical genre, an extraordinary artistic outcome is achieved.

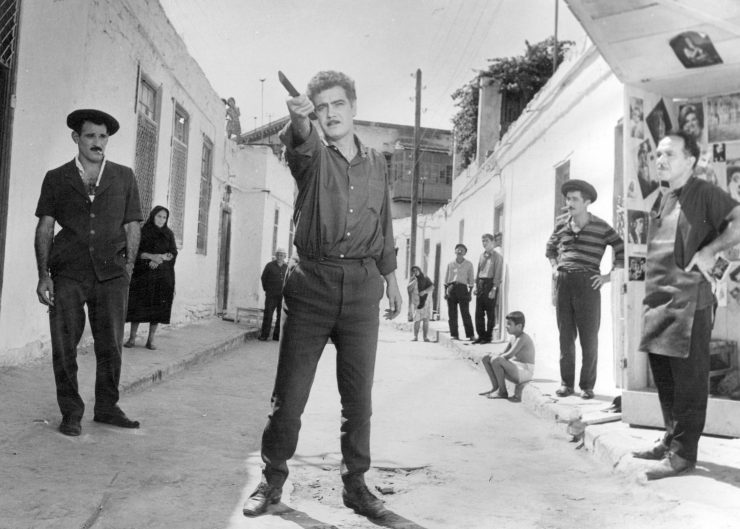

When considering the national aspects of art, we encounter both external expressions, often referred to as “colorfulness” and more profound national characteristics that aren’t immediately apparent. These deeper traits can be elusive because, in the depths of our being, humanity shares a common essence. It’s akin to rocks – they may assume various shapes and unusual configurations, yet they’re fundamentally composed of the same material. The essence of being human remains remarkably similar across different nations, and many fundamental issues are shared universally. These issues span the spectrum of human experience, including social dynamics, interpersonal relationships, and family challenges. Additionally, there are broader concerns, such as how individuals relate to their living environment. An exploration of this latter concern can be found in the film “In This Southern City”, produced at the “Azerbaijanfilm” studio in the late 1960s. This film lingers in my memory because its script was rooted in deeply national material. At its core, the conflict revolved around the fiance of the protagonist’s sister, who brought a woman from Russia into their lives, thereby subjecting his sister and himself to a situation that was both embarrassing and comical in the eyes of their neighbors and numerous relatives. Every resident of this remote street in Baku consider the same and have certain expectations of the hero’s actions. The environment dictated a particular way of behaving, one laden with societal norms and perceptions. The hero, though, attempted to resist this suggested behavioral pattern. He recognized its inherent absurdity but eventually succumbed to it. In contrast, had this tale unfolded in a Russian city, the specifics of life might have been different, even though the hero would likely have still been dissatisfied with his sister’s fiance. It underscores how the particular structure of life is often shaped by human behavior. The reactions themselves might be similar, but how these reactions manifest is undeniably influenced by national characteristics that impact the visual storytelling medium. We can even observe negative examples of this influence in cinemas like Arabic or Indian, where unique systems of imagery and expressions have developed that, at times, lack finesse and artistic credibility. However, within the best works of these cinemas, there are powerful attempts to break free from these stereotypes of expression and language, striving to transcend foreign national characteristics.

Indeed, this issue is intricate and often remains underexplored. It’s fascinating how even something as seemingly straightforward as the geographical setting, like a hot region, can profoundly influence the physicality, ambiance, and descriptive language of a work of art. Consider, for instance, Albert Camus’ “The Stranger.” Throughout the story, the relentless heat and scorching sun permeate the narrative, eroding the characters’ capacity for rational thought. This thematic element necessitates the search for appropriate tools of expression and language. In my view, the well-known Italian-French adaptation of this story faltered precisely due to its inability to find a cinematic equivalent for this pervasive image of oppressive heat.

In conclusion, I would like to address a common methodological mistake frequently made by both our critics and film theorists: This mistake revolves around the misunderstanding of the underlying themes and subjects of a film, which ultimately form its essence. It is often assumed that if a film is set during a war, its theme must inherently be war itself. However, this assumption doesn’t always hold true, and it leads to incorrect analyses of the film’s deeper meanings. This discrepancy becomes particularly evident when filmmakers attempt to transcend the immediate event they depict and explore broader thematic territories.

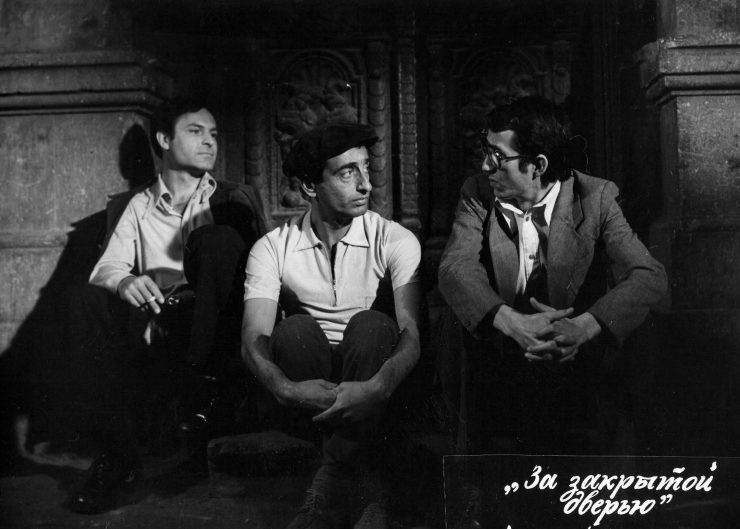

A prime example to illustrate this point is the movie “Behind Closed Doors”. On the surface, it portrays the lives of the inhabitants of a small yard, seemingly limited in scope. However, the core conflict that drives the narrative originates from the modern human’s innate ability to evade involvement in addressing common societal issues. In our era, a certain type of individual has emerged, possessing an instinctual power to rationalize their non-participation in resolving collective problems. These are individuals of integrity in the sense that, given a choice, they would muster the strength to fulfill their duties and moral obligations. Yet, they have developed a biological defense mechanism that allows them to distance themselves from problem-solving long before a definitive “yes” or “no” situation arises. This phenomenon is one of the central dilemmas of our time, the pervasive issue of evading responsibility, which holds significance across all strata of society. In “Behind Closed Doors,” we sought to explore this issue through the lens of life within a small courtyard. Drawing from my own upbringing in such an environment, I’ve recognized interesting artistic possibilities within this setting. This yard, in essence, serves as a microcosm, a model that magnifies the dynamics of this issue and allows us to portray it in a compelling and authentic manner.

Certainly, there are critics who perceive the film as a story confined to domestic settings, reducing it to a tale about a mere courtyard and even when talking about the problem of the film, they close it only with the yard where the incident took place. This limited perspective often stems from the interchangeable use of the terms “subject” and “material,” as well as the difficulty in recognizing the broader implications within the specific context. It’s worth noting that filmmakers themselves sometimes contribute to this issue by not selecting the most suitable cinematic language to effectively convey the underlying problem they aim to address. Thus, it becomes evident that the language of cinema and the imaginative framework employed are of paramount significance in this regard.

Translated from Russian into Azerbaijani by Laman Abbas

The original article was published in the book “What is film language?” (“Что такое киноязык?”) in “Iskusstvo” (Moscow) publishing house in 1989.