Anecdote – a film that destroys itself

The film “Anecdote” directed by Yefim Abramov and Nizami Musayev, skillfully resurrects the vivid, yet also somber, scenes of the late 1980s. The narrative of the film, written by Rovshan Aghayev, commences with the illumination of the stage lights within the party committee secretary’s room. As the darkness dissipates, the first uttered word is “light,” serving as a symbolic inception of the shooting process. From that point onwards, nothing remains concealed in obscurity, for the camera is rolling, and the spotlight is ablaze. This poignant opening serves as a harbinger, gradually unveiling themes of reconstruction, transparency, corruption, capriciousness, freedom, and the disintegration of the USSR, piece by piece.

Karimov found himself desperately trying to evade the pursuing mob, his sole glimmer of hope resting in the idea of seeking refuge within the reception area of the first secretary of the party. Little did those who anxiously waiting in his reception room know, the party secretary was engrossed in a clandestine task, one shrouded in mystery. Various young individuals, hailing from diverse plants and factories, took their turn to introduce themselves, pledging their allegiance to the party. The secretary didn’t keep them in suspense for long. He disclosed his unconventional plan, expressing his intent to instruct them in the art of dancing to a different tune, quite literally. These dances, far removed from tradition, encompassed genres like metal, punk, and rock – deemed by some as “harmful” bourgeois practices. The objective? To tame these unconventional rhythms, to practice them until they became indistinguishable from their counterparts, and ultimately, to infiltrate and dismantle those they deemed repugnant from within. Those awaiting their turn in the reception room remained unaware of the covert activities unfolding behind closed doors.

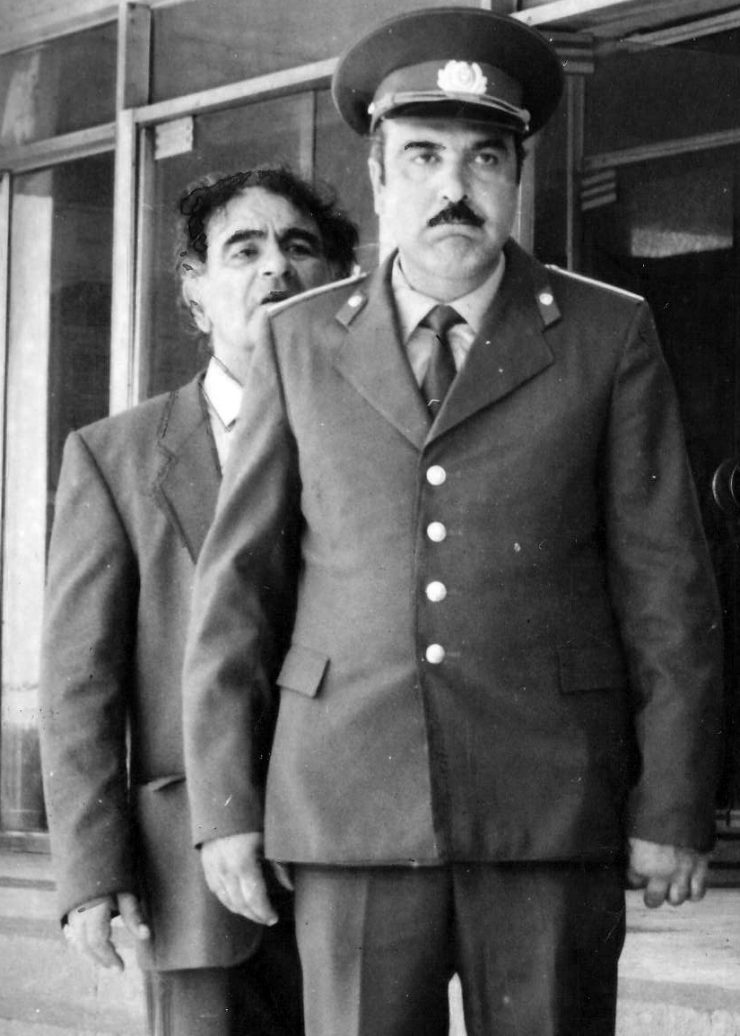

The final addition to the secretary’s reception room and office comes in the form of two individuals intent on reaching the upper floor. Upon glimpsing a woman, they decide to ride the elevator together, only for their ascent to be abruptly halted, trapping them inside. In a poignant moment, one of them remarks, “The elevator works like their government,” a powerful reflection of the film’s unapologetically anti-Soviet stance, reiterated throughout. With the film confined to just three locations, a palpable sense of claustrophobia begins to envelop the narrative. Those marooned in the reception room, alongside those trapped in the malfunctioning elevator, grapple with a sense of helplessness. Meanwhile, outside on the street, a growing crowd rallies and voices their grievances through slogans. These slogans, while devoid of explicit political undertones, center on the pressing issue of the inadequate sewage system in the newly constructed micro-region. Rahimov, portrayed by Rasim Balayev, cynically observes that this pattern is all too familiar—construction of micro-regions without proper sewage infrastructure—a commentary on the recurring themes of inefficiency and bureaucratic neglect.

The events within the secretary’s room are primarily characterized by captivating dance sequences, while within the elevator, a chorus of desperate pleas for escape resonates. Notably, Mamed and Ahmed have brought with them a bomb, their sinister plan to obliterate the entire building. The presence of Rimma remains an enigmatic figure. Following these intriguing introductory scenes, the narrative focal point shifts towards the secretary’s reception room. Here, an eclectic mix of individuals with diverse backgrounds and aspirations converge: a prosecutor, a person seeking to travel abroad despite being deaf-mute, a dedicated school principal, and a distressed mother on the verge of taking her own life due to her son’s predicament.

The sudden entry of the construction manager into this eclectic mix adds a surprising twist, while the arrival of the police further underscores the escalating chaos and their struggle to maintain control. The situation unfolds like the setup of an anecdote: “One day, three people find themselves trapped in an elevator. Another day, a motley group assembles in the secretary’s reception room,” weaving a captivating tapestry of suspense and human complexity.

Upon entering the room of the mother, whose son had been unjustly arrested, a wave of unease washes over the people who had patiently awaited their turn. The tension that had been simmering beneath the surface finally erupts. The mother’s stark declaration of her desire to end her own life, accompanied by the blunt statement, “I spit on such a government,” perfectly encapsulates the overarching theme of the film. The prosecutor attempts to persuade her, while Rahimov endeavors to dissuade her from her suicidal thoughts. The mother’s anxiety gradually subsides as she receives assurance that her son will be released. In this moment, the filmmakers employ an intriguing visual technique, altering the image’s color (sometimes yellow, sometimes red, and occasionally black and white) to provide insight into the dreams and fears of each character. One person dreams of taking the podium to deliver a speech, another yearns to become a member of parliament and speak French, and a deaf-mute character envisions unleashing his machine gun to kill them.

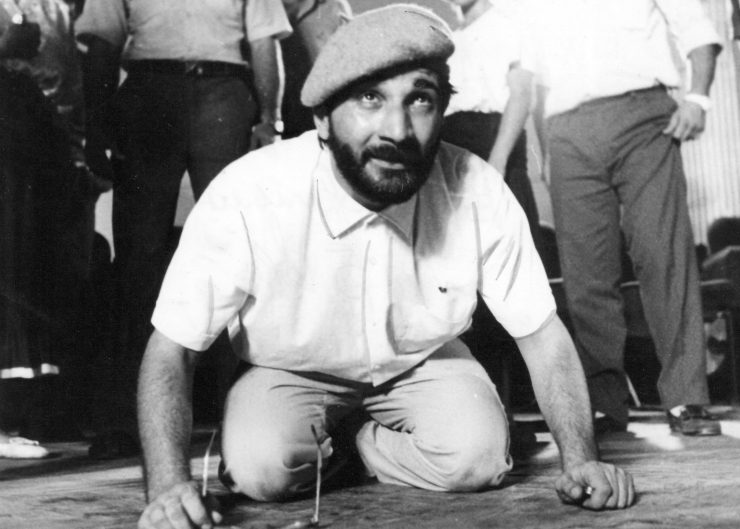

The reception room of the secretary’s office abruptly transforms into a surreal realm reminiscent of Tarkovsky’s enigmatic “Zone.” Within this uncanny space, every occupant is compelled to confront their deepest desires, anxieties, and aspirations. However, this extraordinary encounter serves a more pragmatic purpose rather than being a purely philosophical inquiry. It becomes a means to penetrate the core of these characters, delving into their innermost selves. In the absence of external conflicts within this confining chamber, it becomes the crucible where their past and true identities are unveiled. At times, Mamed, played by Yashar Nuri, and Ahmed by Ajdar Hamidov, resort to desperate pleas, their voices reaching skyward. They even gazing directly into the camera and exclaiming, “Freedom, freedom!” Through this audacious move, the creators inject the pressing social challenges of their era directly into the realm of cinema.

The initial cheerful mood and light-hearted humor in the film gradually succumb to the weight of political appeals and social messages. Javanshir Guliyev’s accompanying music, which amplifies the solemn and tense atmosphere, leaves little space for laughter. Consequently, just like the characters on screen, the audience finds themselves devoid of comfort. Consequently, the film’s balance between humor and tragedy tilts towards the latter, rendering the dialogues less amusing and, most significantly, more thought-provoking. What transpires among the characters, their hypocrisy, the complete erosion of their morals, and the loss of their identities become all the more pronounced through these tragic elements. (1st November)

Verticality pervades both the spaces inhabited by “Anecdote” and the broader societal structure. When people are out protesting, demanding basic amenities like a sewer system, it’s important to remember that individuals like Ahmed, who find themselves trapped in elevators, are dealing with urgent, everyday needs as well – like the need for a restroom. Ahmed stands as a representative of the ordinary folks in the crowd; he doesn’t harbor grand ambitions or lofty dreams. His motivation is simple: he requires money, and this pressing need has driven him to bring a bomb into the building. Mamed shares a similar plight to Ahmed, and together, they symbolize the plight of the helpless working class, often referred to as proletarians.

On the other hand, those gathered in the secretary’s reception room can be seen as representatives of the middle class. Even though they might be aware of the dire situation unfolding in the elevator and the protests raging below, they tend not to take decisive actions to address these issues. They fabricate falsehoods on the fly and anticipate that everyday folks will swallow them hook, line, and sinker. The proof was in the pudding when the crowd dispersed right after Rahimov’s speech. He brazenly claimed that the first secretary had been dismissed, a total fabrication. The secretary couldn’t care less about any of this; his primary concern is these young folks who are into rock and metal music. If he can somehow eradicate their influence, he believes all of our problems will magically disappear. The ruling elite remains blissfully ignorant of the struggles faced by the working class, and they have no inclination to change that. They remain steadfast in their belief that the solutions they come up with, no matter how hollow they may be, even if it has no positive impact on people’s lives…

Individuals trapped within confined spaces evoke a vivid parallel with the collapse of the USSR for the audience. Even for the authors who may fear that their narrative, laden with symbols and metaphors, won’t be fully comprehended, Mamed ingeniously provides another opportunity to directly engage with the audience. He cautions the people, emphasizing that if this course persists, everything will face destruction. While the hero here speaks of the impending bomb detonation, he simultaneously diagnoses the state of society.

The movie culminates in a truly unforgettable manner as the film’s creators reveal their identities, willingly embracing their impending doom. As the iron grip of military forces tightens its hold on power, Stalin makes a formidable appearance on the screen, delivering a resounding speech on the revolution and the lurking internal threats. Lastly, the tension escalates further as the creative team, their faces etched with the unmistakable signs of guilt, is depicted in prisoner attire, labeled as criminal cases. This seemingly drastic step is their safeguard against the scathing criticism they anticipate. Even during an era marked by a purported commitment to transparency and reconstruction, the indelible marks left on the artists of 1937 persistently echo through collective memory. As the film approaches its conclusion, a bomb detonates, symbolizing a cataclysmic climax. The once-bright beacon of hope, kindled at the film’s inception, ultimately succumbs to the encroaching darkness that once again envelops society.

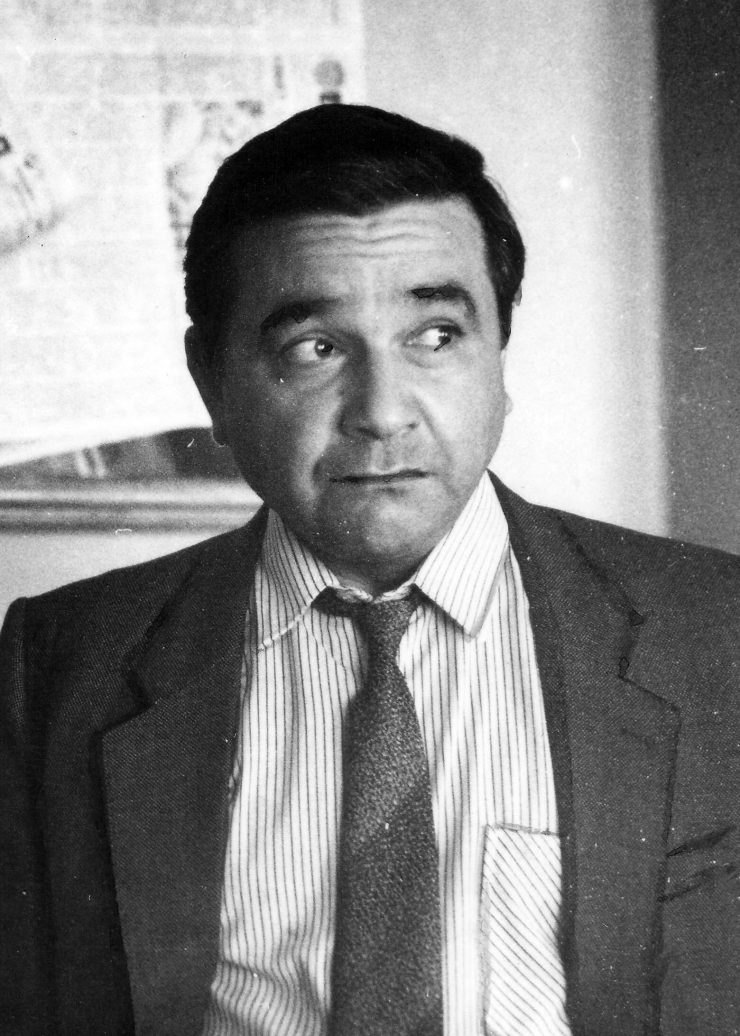

Haji Safarov